Written by Ronald J. Gordon Published: August, 1998 ~ Last Updated: September, 2020 ©

This document may be reproduced for non-profit or educational purposes only, with the

provisions that this document remain intact and full acknowledgement be given to the author.

|

|

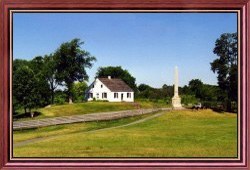

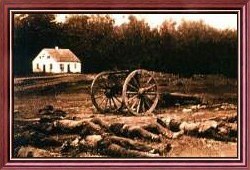

On the crown of a long ridge near the Antietam Creek in north central Maryland, stands a little Dunker Church that continues to render a silent testimony to the horror of a one day battle that surrounded it on September 17, 1862, during the Civil War or the War Between the States. Its gleaming white walls became an early morning goal for the advancing Union army of General George B. McClellan who was attempting to dislodge the Confederate army of General Robert E. Lee from this ridge and prevent his northern advance into Union territory. Around 23,000 troops had been killed, wounded, or missing. Six generals also died in the countryside surrounding this alabaster jewel in what still remains the bloodiest day of fighting in the history of United States warfare. Prominently located next to the old Hagerstown Pike on ground donated to the newly formed congregation by Brethren farmer Samuel Mumma, the little Dunker Church would be surrounded by Confederate forces during morning hours, possessed by Union infantry for brief moments, reclaimed by the Confederacy, modified into a field hospital for wounded and dying soldiers by evening, and finally a post battle refuge for peaceful conversation between both armies the next day.

Early morning light gleaming over South Mountain bathed the white exterior church walls, making its luminescence easily visible to Union officers who instructed their units to move toward it by crossing a thirty-acre corn field. Morning hours saw cannonballs and rifle bullets piercing its walls and studding its rafters. By evening it became a makeshift hospital that heard shrieks of pain and unending moans, this in stark contrast to praises of God and melodies of worship. Sermons echoing victory through the Blood of Christ were disquieted by human blood that splattered defeat on its wooden furniture. Hope was exchanged for despair and life replaced with death. Unimaginable horror continually announced itself through a stream of mangled soldiers being carried into the little Dunker Church, because of its immediate proximity to the Corn Field where most of the morning slaughter had occurred. So furious and chaotic was the maddening exchange of gunfire, canister, and shell cannon in this now famous Miller Cornfield, that Union General Joseph Hooker stated: “In the time I am writing, every stalk of corn in the greater part of the field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife.” A horrific sight of dead bodies, many laying on the ground as if still in formation: “the slain lay in rows precisely as they had stood in their ranks a few moments before” (Hooker). Another unknown witness testified that the Corn Field “was so full of bodies that a man could have walked through it without stepping on the ground.” Union troops had failed to dislodge the Confederate left flank, and would spend the afternoon trying to penetrate their center at the Sunken Road or Bloody Lane and finally on their right at Burnside Bridge. This engagement would be remembered by the Union as the Battle of Antietam because McClellan's headquarters was near this stream, and by the Confederacy as the Battle of Sharpsburg because Lee's headquarters was located in this nearby town.

When the killing and movement of troops finally halted at the end of this one day battle, the lines of entrenchment were not that much different from where they originated that same morning. Although this bloodiest day of fighting produced no clear winner, historians usually give Lee the dishonor of defeat because he was unable to continue his northern advance into Union territory. But it could also be argued as a minor victory for the Confederacy when considering that Lee's 37,000 troops were able to withstand a much larger force of McClellan's 56,000 and that President Lincoln fired McClellan over repeated hesitancy's to capitalize on fortunes of opportunity. Because the Union army possessed almost twice the number of troops, it has been called the battle that McClellan could not lose and Lee could not win.

The magnitude of suffering witnessed on the Antietam Battlefield was nine times greater than the number killed and wounded on June 6, 1944 ( D-Day ) the so-called “longest day” of World War II. Six Generals died in the heat of battle this day, the exact spots where they fell now marked by cannon barrels mounted in concrete. More soldiers were killed, wounded, or listed as missing during this one day of battle than the total number of casualties of all Americans in the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican War, and the Spanish-American War combined. Eye-witnesses stated that the Cornfield / Dunker Church fighting lasted about three hours.

Every second, a husband, father, or son was dying. The stillness of a quiet countryside heard the roar of cannons and the agony of men. Sweet air was exchanged for the smoke of gunpowder. All before the Little Dunker Church where the Brethren preached a message of peace and non-violence.

|

|

Visitors to the Antietam Battlefield stand in quietude or respectfully walk over its hallowed grounds. They read the large historical markers erected by the National Park Service, looking intensely at the view just beyond, trying to imagine how it must have appeared during that respective phase of the battle. A few take pictures while others check maps and brochures. They come from all parts of the world to feel history, to be enveloped in the mesmerizing wonderment of artifacts, stories, and photographs. Only when the physical eye has seen the landscape does one actually feel apart of the experience. Sharpsburg is a small town of about six hundred and fifty-nine people (1990 Census) and only 14 miles south of Hagerstown, Maryland>, along Route 65, yet lost from the notice of most tourists and war enthusiasts. Whereas, Gettysburg receives almost two million visitors every year to its battlefield memorial park, Antietam gathers only a few hundred thousand because it requires a dedicated effort, just to find its location.

This picturesque community resides among the beautiful hills of the north-central Maryland countryside, miles from Interstate highways and major airports. No plethora of hotels and fast-food restaurants as in Gettysburg or Richmond. This town has not experienced much growth since the battle, and because of the scarcity of overnight accommodations, visitors should plan to bring their own food and then leave before nightfall, in order to return to nearby motels in Hagerstown. Perhaps, the visitor to Antietam comes for a more specific reason. What do they hope to find? ...history? ...genealogy? ...religion? ...ghosts? ...themselves? Our story is about the Dunkers, their historical witness for peace and non-violent resolutions, and the monumental battle that confronted that witness. |

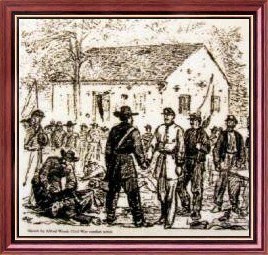

Sketch artists preceded battle photographers by many years. Brush and oil captured the pageantry of victory, horribly juxtaposed with the gruesome contortions of those slaughtered. From charcoal stick figures of cave paintings to the breathtaking murals of Antoine-Jean Gros. On the day following the battle, Alfred Waud stood before the Little Dunker Church and immortalized this peaceful scene of Union and Confederate soldiers talking with each other. It was paradoxical. Bewildering. Yet, strangely fascinating. |

|

The previous day they had fiercely struggled to kill each other on these very grounds, and now before Waud's pencil they corporately mused over the hideous import of their actions. The Army of Northern Virginia would soon head west, crossing the wide Potomac river, while the Army of the Potomac would wait for Lincoln to clarify their mission. Weary men from each army would never forget this bloodiest day of battle, and how they finally enjoyed peace - in front of that Little Dunker Church. |

Photo Credits:

- All modern photographs by Ronald J. Gordon ? 1998, 2000, 2002

- Civil War photographs displayed in compliance to all known Copyrights

- Sketches drawn by noted battlefield artist Alfred Waud, Photo at Gettysburg

Literary Sources:

- A Century of Faithful Service - The Sharpsburg Church of the Brethren, 1899-1999

- Antietam: Photographic Legacy - William Frassanito, Thomas Publications, 1978

- Beliefs Of The Early Brethren - William Willoughby, Brethren Encyclopedia, 1999

- Change and Challenge: Pennsylvania Southern District - by Elmer Gleim, Triangle Press, 1973

- Heritage and Promise: Perspectives on the Brethren - Emmert Bittinger, Brethren Press, 1970

- History of the Church of the Brethren in Maryland - J. Maurice Henry, Brethren Press, 1936

- Land Tracts of the Battle of South Mountain - Curtis Older, Family Line Publications

- Sidelights in Brethren History - Freeman Ankrum, Brethren Press, 1962

Documents:

- A Woman's Recollections of Antietam - Mary Bedinger Mitchell

- Emancipation Proclamation

- Huckleberry Finn, The Adventures of - Mark Twain, 1851

- Juneteenth Independence Day - J.C. Watts, Jr.

- Lee, General Robert E.

- Military Reports of Antietam

- Cox - Major General Jacob D. Cox

- Early - Lieutenant General Jubal Anderson Early

- Gordon - General John B. Gordon

- Hill - Lieutenant General Daniel H. Hill (Confederate Side of the Battle)

- McClellan - General of the Army of the Potomac, George B. McClellan

- Stuart - Major General J.E.B. Stuart

- Toombs - General Robert A. Toombs

- Statement of the Church of the Brethren on War - This statement formalizes earlier beliefs into written form. It was first adopted by the 1948 Annual Conference as the "Statement on Position And Practices of the Church of the Brethren in Relation to War." A first revision was later made in 1957, and a second in 1968. It appears here as revised for the third time by the 1970 Annual Conference.

Abraham Lincoln, Sixteenth US President:

- Lincoln Online: Presidential Papers, Biography, Speeches

- On Preserving Liberty: Addresses, Debates and Letters

- Response to New York Tribune Editor Horace Greeley on Published Criticisms

Alexander Gardner, Photographer of Antietam:

- A Biography of Alexander Gardner

- A Biography of Matthew Brady

- About Civil War Photography

- Captured in Black and White: A History of Civil War Photography

- Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book, 1866, New York: Dover Publications, Reprint 1959

- Life and Photographs of Alexander Gardner by D. Mark Katz

- Library of Congress - American Memory Library of Civil War Photographs

- Matthew Brady - A Biographical Note

- Taking Photographs during the Civil War

- Wet Plate Negatives

Brethren Resources:

- Brethren Groups (Denominations using the label of Brethren)

- Church Of The Brethren - Official Statement On War

- Conscientious Objection to War

- On Earth Peace Assembly

- Peace & War by Ronald Gordon

- Sharpsburg Church of the Brethren

- The Little Dunker Church by Peter Haynes - In the early 1960's, Brethren minister and historian, Freeman Ankrum, wrote a book entitled, Sidelights on Brethren History, ? Brethren Press, 1962, which contained several chapters related to the story behind this Dunker meetinghouse in the days and years surrounding the battle. Haynes includes the following chapters from the book: Antietam Incidents, Troubles Over Slavery, David Long: Civil War Preacher, and John Lewis and the Antietam Bible.

Clara Barton: Angel of the Battlefield

- Ambulance Corps of the Union Army

- American Red Cross Founder

- Biography of Clarissa Harlowe Barton

- Civil War Nurses

- Medicine During the Civil War

- Monument to Clara Barton at Antietam National Battlefield

- Missing Soldier's Office (GSA)

- Missing Soldier's Office (NAIS)

- National Park Service: Historic Site

- Sketch of a Civil War Hospital by Louisa May Alcott

- Women Who Went to the Field by Clara Barton

Maps of Antietam:

- 1890 Army Survey

- 1890 Army Survey with Color added by Brian Downey

- Location of Dunker Church (MapQuest)

- National Park Service 203K

Peace Resources:

- American Friends Service Committee

- Christian Peacemaker Teams

- Center On Conscience (formerly NISBCO - National Interreligious Service Board for Conscientious Objectors)

- Flags In the Sanctuary

- Pennsylvania: The Quaker Province 1681-1776

- Trained To Kill - Lt. Colonel David Grossman

- Who Are the Historic Peace Churches

Web Sites:

- 360º & Wide Angles

- 150th Anniversary of the Civil War

- Antietam National Battlefield - U.S. National Park Service

- Antietam, Battle Of: (Antietam.Com)

- Antietam, Battle Of: (Civil War Home)

- Antietam, Battle Of: (Military History)

- Antietam, Battle Of: (Antietam on the Web)

- Biographies of the Civil War

- Carry Me back to Old Virginia

- Cavalry

- Description of a Typical Confederate Soldier

- Description of a Typical Soldier

- Emancipation Proclamation

- Information on Civil War Topics Listed Alphabetically

- Lodging & Dining

- Medicine During the Civil War

- Military History in 1861

- Military Intelligence During the Maryland Campaign

- Napoleonic Battle Formations

- Overview of American Civil War 1861-1865

- Panoramic Views of Antietam

- Resource Use and Privacy Statement of the National Park Service

- Rifled Musket and Cannon

- Slain Lay in Rows - Peter Carlson, The Washington Post

- Staff Ride Guide: Battle of Antietam

- Slavery

- African Slave Trade & European Imperialism

- Chronology on the History of Slavery and Racism

- Dred Scott Decision of 1857

- How Did American Slavery Begin

- Internet Sources on the Origins Of Slavery

- Re-Evaluating John Brown's Raid At Harpers Ferry

- Restriction of Legal Rights for Slaves in Virginia and Maryland

- The Slave Kingdoms: Dahomey and Ashanti

- South Mountain: Fire at Turner's Gap

- Timelines

- Weaponry

- Who Lost the Lost Order?