Written by Ronald J. Gordon Published: August, 1998 ~ Last Updated: March, 2013 ©

This document may be reproduced for non-profit or educational purposes only, with the

provisions that this document remain intact and full acknowledgement be given to the author.

|

|

Modern warfare has evolved into a push-button activity where the shooter rarely witnesses the actual carnage from the effect of bullets, missiles, shells, and bombs. It has evolved into a faceless and nameless process of engagement and prosecution. But during the Civil War, fighting between troops usually meant killing one another in close quarters, and quite often face to face. As a soldier, you had the wretched opportunity to behold the very look of anguish on the face of the enemy when he reeled from the jolting impact of your bullet, as well as the distant cataclysmic image of shells and canisters ripping into multiple figures at the same time. You saw the distorted faces of pain, shrieking in agony as their insides were ruptured, as blood gushed past their crippled arms. You stepped over lifeless bodies as your Regiment or Company advanced through the lines. Ancient close quarter warfare caused immense suffering. Those who were not killed instantly, often died a prolonged death of agony because of improperly dressed wounds or lack of any medical attention. Battlefield statistics do not reveal the countless number of personal stories of excruciating injury or the incalculable amount of brokenness to families. One unknown commentator has remarked: “Statistics are people with the tears wiped from their eyes.” Let us now look into the eyes of the people who were at Antietam; the eyes of generals, sons, nurses, photographers, bystanders, souvenir hunters, and of course the Dunkers. Faces tell stories that cause us to halt and ponder. Eyes make us sense reality. What if that were my dead son in that photograph? What if that was the lifeless body of my husband? It was not just twenty-three thousand men who died that day, it was the throes of a divided nation, a newly formed Republic whose philosophical foundations were being threatened to the very underpinnings.

In our modern faceless society of online connections and supersonic travel, we too often fail to see the beauty of eyes. Only when speaking face to face can we really experience the inner qualities of people. When we first begin talking with someone, face to face, it is their eyes that becomes our point of focus. At an early age we learn that this type of intimate conversation usually involves a continuous shuffling of intermittent glances. Each person wants to grant the other a gaze of respect, but not too long, that such would be considered an offensive stare, yet often enough so as not to appear distant or aloof. Telephones and letters communicate well but are no substitute for seeing the eyes. In the following eye-witness accounts, we shall learn a great deal about that day of battle. We must somehow attempt to look through the eyes of the following people who personally experienced the throes of Antietam. Open your imagination to witness the battle as it must have appeared through their eyes.

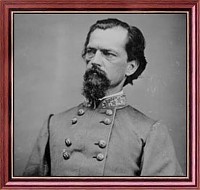

General John B. Gordon |

In the battlefield description of Confederate General John B. Gordon (no relation to this writer), we are given a vivid account of an episode at Bloody Lane, with an astonishing glimpse of soldiers commanded to use bulletless chambered rifles, in order to break through the enemy line with bayonet only. During the morning hours near the Little Dunker Church, Gordon witnessed the devastation of brigades and divisions, as he walked around bodies piled upon bodies. At mid-day, Union formations marched upon Gordon’s unit that lay prostrate in the Sunken Road. His personal record captures the futility of war and the hopelessness of battlefield machinations. John Brown Gordon was a native of Georgia and a distinguished graduate of the University of Georgia. After turns at law and journalism, he enlisted in the army. Many of the Confederate officer Corps were professionally trained soldiers that gave little admiration to their superior officers, because the latter were often notable civilians granted the privilege of a high ranking commander. Gordon was one of a few civilian-turned-soldier who possessed an incredible degree of respect from his men - in all ranks. General Robert E. Lee described him to Confederate President Jefferson Davis as “one of my finest brigadiers.” After the war, he became the first Confederate to preside over the United States Senate, and to have the New York Times call him “the ablest man from the South in either House of Congress.“ Future President Theodore Roosevelt remarked: “A more gallant, generous, and fearless gentleman and soldier has not been seen by our country.” While fighting at Antietam, General Lee assigned him to hold a vital position in a sunken road which later became known as the Bloody Lane. The scene that Gordon describes in these brief selections from his official report can only be described as stupefying. The visitor will be entreated to the full experience and horror of men killing each other in the most intentional manner, for this is the life of the devoted soldier, to kill in the most effective way possible while losing the least amount of your own resources. Gordon was incredibly outnumbered by the onward marching Union ranks, and instructed his men to fire only upon his few commands, because their store of ammunition had not been resupplied.

"The brave Union commander, superbly mounted, placed himself in front, while his band in rear cheered them with martial music. It was a thrilling spectacle. The entire force, I concluded, was composed of fresh troops from Washington or some camp of instruction. So far as I could see, every soldier wore white gaiters around his ankles. The banners above them had apparently never been discolored by the smoke and dust of battle. Their gleaming bayonets flashed like burnished silver in the sunlight. With the precision of step and perfect alignment of a holiday parade, this magnificent array moved to the charge, every step keeping time to the tap of the deep-sounding drum. As we stood looking upon that brilliant pageant, I thought, if I did not say, ‘What a pity to spoil with bullets such a scene of martial beauty!’ But there was nothing else to do. Mars is not an aesthetic god.

Every act and movement of the Union commander in my front clearly indicated his purpose to discard bullets and depend upon bayonets. He essayed to break through Lee’s centre by the crushing weight and momentum of his solid column. It was my business to prevent this; and how to do it with my single line was the tremendous problem which had to be solved, and solved quickly; for the column was coming. As I saw this solid mass of men moving upon me with determined step and front of steel, every conceivable plan of meeting and repelling it was rapidly considered. To oppose man against man and strength against strength was impossible; for there were four lines of blue to my one of gray. My first impulse was to open fire upon the compact mass as soon as it came within reach of my rifles, and to pour into its front an incessant hail-storm of bullets during its entire advance across the broad, open plain; but after a moment’s reflection that plan was also discarded. It was rejected because, during the few minutes required for the column to reach my line, I could not hope to kill and disable a sufficient number of the enemy to reduce his strength to an equality with mine. The only remaining plan was one which I had never tried but in the efficacy of which I had the utmost faith. It was to hold my fire until the advancing Federals were almost upon my lines, and then turn loose a sheet of flame and lead into their faces. I did not believe that any troops on earth, with empty guns in their hands, could withstand so sudden a shock and withering a fire.

The programme was fixed in my own mind, all horses were sent to the rear, and my men were at once directed to lie down upon the grass and clover. They were quickly made to understand, through my aides and line officers, that the Federals were coming upon them with unloaded guns; that not a shot would be fired at them, and that not one of our rifles was to be discharged until my voice should be heard from the centre commanding ‘Fire!’ They were carefully instructed in the details. They were notified that I would stand at the centre, watching the advance, while they were lying upon their breasts with rifles pressed to their shoulders, and that they were not to expect my order to fire until the Federals were so close upon us that every Confederate bullet would take effect.

There was no artillery at this point upon either side, and not a rifle was discharged. The stillness was literally oppressive, as in close order, with the commander still riding in front, this column of Union infantry moved majestically in the charge. In a few minutes they were within easy range of our rifles, and some of my impatient men asked permission to fire. ‘Not yet,’ I replied. ‘Wait for the order.’ Soon they were so close that we might have seen the eagles on their buttons; but my brave and eager boys still waited for the order. Now the front rank was within a few rods of where I stood. It would not do to wait another second, and with all my lung power I shouted ‘ Fire !’

My rifles flamed and roared in the Federals’ faces like a blinding blaze of lightning accompanied by the quick and deadly thunderbolt. The effect was appalling. The entire front line, with few exceptions, went down in the consuming blast. The gallant commander and his horse fell in a heap near where I stood - the horse dead, the rider unhurt. Before his rear lines could recover from the terrific shock, my exultant men were on their feet, devouring them with successive volleys. Even then these stubborn blue lines retreated in fairly good order. My front had been cleared; Lee’s centre had been saved; and yet not a drop of blood had been lost by my men. The result, however, of this first effort to penetrate the Confederate centre did not satisfy the intrepid Union commander. Beyond the range of my rifles he reformed his men into three lines, and on foot led them to the second charge, still with unloaded guns. This advance was also repulsed; but again and again did he advance in four successive charges in the fruitless effort to break through my lines with the bayonets. Finally his troops were ordered to load. He drew up in close rank and easy range, and opened a galling fire upon my line.

The fire from these hostile American lines at close quarters now became furious and deadly. The list of the slain was lengthened with each passing moment. I was not at the front when, near nightfall, the awful carnage ceased; but one of my officers long afterward assured me that he could have walked on the dead bodies of my men from one end of the line to the other. This, perhaps, was not literally true; but the statement did not greatly exaggerate the shocking slaughter. Before I was wholly disabled and carried to the rear, I walked along my line and found an old man and his son lying side by side. The son was dead, the father mortally wounded. The gray-haired hero called me and said: ‘Here we are. My boy is dead, and I shall go soon.’"

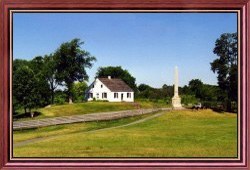

Gordon’s vivid eye-witness descriptions of the events on the Antietam battlefield become horrifyingly real to us. Through his eyes we see the carnage of scattered bodies and confounded logic, as men begin killing each other at close range in the Bloody Lane, charge after charge after charge. Men died by the thousands that day, within a few minutes walking distance of the Little Dunker Church where the message of non-violence was preached.

John S. McCarthy |

Directly in front of the Little Dunker Church passed the 125th Pennsylvania Volunteers of Crawford’s brigade in Williams’s division of the Twelfth Corps. More lives were lost in the Miller Cornfield than any other part of the battlefield. Entire brigades had been obliterated. The ground surrounding the Dunker Church would change hands several times as the Union advanced upon retreating Confederates, only to experience charging Confederates driving segmented Union forces back toward the East Woods, and then the shuffling would repeat. Fragmentation was ubiquitous as clusters of soldiers charged ahead while comrade units fell dead to their left and right. As these forward isolated units then waited and waited for resupply, the enemy would gain strength and drive them into full scale retreat; and then the whole pattern commenced again. One commentator described it as a bizarre form of line dancing. In one of those detached units we find private John S. McCarthy, in uniform only a month before Antietam. The 125th Pennsylvania Volunteers had actually penetrated the West Woods around the Dunker Church, which was at first thought to be a School House, as seen from across the Miller Cornfield in the East Woods. He was only twenty-three years old, the son of a farmer who decided to enlist. McCarthy was born on a 134 acre farm in Airy Dale, Pennsylvania, in 1839, located in what is now called Big Valley. It has some of the best farms in Pennsylvania. Not disregarding the small amount of industry to be found in this region, modern Huntingdon County is still largely a clustering of farming communities. If resurrected, John McCarthy could almost return to the same farmlands and ridges that he once knew - almost. Second eldest child in a family of nine, McCarthy accepted the elder son responsibilities of farm life since his father was often ill from the effects of a spinal disease. The first year of the war, he remained on the farm but was irresistibly drawn into the mass appeals for troops during the next summer. Company H, 125th Pennsylvania Volunteers received a new recruit on August 13, 1862. Leaving from the Huntingdon railroad station, his thoughts must have been typical of a young man bound for war, as the train meandered along the winding curves of the Juniata River on its way to Harrisburg and later to Washington, DC. Was he thinking of his parents and siblings? ...his home community? ...of President Lincoln? ...of slavery? Probably all of these and much more. Was he thinking of a special girl? One that he would liked to have dated but never asked? Is her face etched in his mind beside parents and friends? How can we ever know the full expanse of the throughs and feelings of men as they go off to war?

John and the rest of his brigade having progressed beyond the Miller Cornfield, were ordered to lie down along the Smoketown Road which runs directly to the Dunker Church. Soon, they found themselves in a most awkward situation. They were alone, having ran beyond the rest of their unit. All around them dead bodies lay against each other in the most helpless and contorted positions - a mangled collection of youthful dreams never to be achieved and family memories not to be known again. During a brief lull in the fighting, John and his combat buddies would have the opportunity to rest and meditate on their present circumstance. Were they speaking to each other out loud, solemnly anticipating their immediate future, or wishing for the security of home? If we could look into John’s eyes, what would they reveal? Is John thinking about his parents? ...that girl? ...Big Valley? ...slavery? ...Lincoln? ...just staying alive? Before long a mounted officer galloped up and ordered commander Jacob Higgins to advance into the West Woods that surrounded the Dunker Church.

There had been a lot of killing thus far under a drizzling canopy of clouds, but the greatest number of men to actually fall at any one time was about to occur. John with rifle in arms ran down the road toward the Dunker Church with his buddies. He was only yards away from a Church which believed that men should not take up weapons against their enemies. The Dunkers preached that men and women should live in harmony with God, and each other. Sermons of this denomination resounded the biblical call of Jesus to be peacemakers. There were Dunker congregations back home in Big Valley. Did John know about their beliefs? Did he even know that this building was a church as he crossed the Hagerstown Pike and into the West Woods? Union officers first thought it to be a School House. John was so close to the Dunker message of peace as he followed commander Higgins into the thicket of the West Woods. It was about 10 a.m. and the men were tired from hours of intense fighting. Several men from these advancing units looked in the door of the Dunker Church to find Confederate soldiers lying on pews and scattered around on the floor. Modern accounts tell of it being made into a field hospital but Civil War historians convincingly argue that it was more probably a forward medical dressing station, where wounded soldiers were gathered before removal to the field hospitals that were always well behind the lines of fighting. Blood was everywhere. Splattered on the wooden furniture, and gathering in pools on the floor. Was John McCarthy one of the curious? Did he stand there looking inside this Church that preached a message of peace? Did he ever come to know what these Dunkers believed? We pause to remember the words of Jesus as he wept over the city of Jerusalem: “And when he was come near, he beheld the city, and wept over it, Saying, If thou hadst known, even thou, at least in this thy day, the things which belong unto thy peace! but now they are hid from thine eyes,” Luke 19:41-42.

It was a brilliant tactical maneuver. Out-flank the Confederate left and reach the nearby Potomac River where the Federals would hopefully cut off their immediate retreat. It almost worked. Confederate General Stonewall Jackson’s troops were nearly obliterated by Hooker’s Union cannon fire while standing in the Miller Cornfield, and were forced to retreat back past the Dunker Church. John Sedgwick’s division of Edwin Sumner’s 2 Corps made it across the Cornfield and into the West Woods. But unknown to these men, the newly arrived Confederate reinforcements of Lafayette McLaws and Joseph Walker would come pouring through these woods and inflict upon Sedgwick’s troops, the most disastrous number of casualties of the day for any short period of time. 2,200 men would die from close range fire in about twenty minutes. Nothing more is known about John McCarthy after this time. He never returned home. Was his lifeless body looted by enemy soldiers? Both Union and Confederate armies routinely looted dead soldiers, taking needed equipment and money, with personal items as souvenirs. What happened to John McCarthy in those final moments as he saw a thunder of fire coming toward him. Did he think about the Dunker message of peace? ...his parents? ...that girl that he never asked for a date? ...Big Valley? ...Lincoln? ...slavery? No one will ever know except the peaceful West Woods that lies just beyond the Little Dunker Church.

NOTE: This story has been collated from the public testimony of numerous witnesses of the events, and expanded from the original story written by William Frassanito as found in Antietam: Photographic Legacy, Thomas Publications, 1978.

Clarissa Harlowe Barton |

Across the plains and hillsides of the Antietam battlefield were collections of dead soldiers, interspersed with a few living men who mournfuly groaned and pitifully begged for help. Rifle and cannon fire had ceased as both armies concluded the day with a virtual stalemate. Lee had successfully held this ridge but could progress no farther north. McClellan could not take the ridge but was content to have halted Lee’s northern advancement, a decision of hesitancy that would later cost him his job. The magnitude of suffering was horrendous. Witnesses described the post battle scene as ghastly collections of decomposing flesh, bloated bodes exuding the most revolting stench, a graveolent putridness that would soon be detected over the entire twelve square mile area of the battlefield. The very distinctive odor of human excrement was unmistakable, exuded by internal gaseous pressure from already diarrhetic soldiers. Union burial details faced a mammoth enterprise of collecting twenty-three thousand bodies, transporting them to designated areas for burial, and then hand digging each grave. Internment was not completely finished until late in the evening of September 21. Four whole days. Occasionally, perhaps to hasten the physically exhausting process, not all bodies were transported to one mass graveyard. Smaller cemeteries distributed across the battlefield might have a lone wooden marker reading: “80 Confederates buried here.” Field hospitals began their operations as soon as they could establish a safe base that was reasonably distant from the actual fighting. In most cases due to unexpected conditions, this was accomplished several hours after the battle had actually started. But their heaviest demand was in the succeeding hours and days when peace on the battlefield permitted the full number of wounded to be transported under less intense conditions. Field hospitals could be make-shift tents, barns, or railroad stations. The environment was sickening and fraught with the most tragic pleas for assistance.

During ancient warfare there was no organized logistical plan to care for the wounded. Fallen soldiers were often the helpless prey of the enemy, local citizenry, or wild animals. Even the Bible records narratives of wounded soldiers begging to be put out of their misery (2 Samuel 1:9). Napoleon was the first to assign special details of litter-bearers to move the wounded, composed mostly of inept soldiers who could not handle much additional responsibility. It was realized that some wounded soldiers could be returned to battle, if their wounds were quickly dressed and proper medication was applied. This was a strategic improvement over the ancient practice of discarding wounded comrades as though dead. George Washington used this same idea for his army during the Revolutionary War. Still, there was no specialized logistical plan developed for processing battlefield wounded. This may be attributed in some degree to small numbers of wounded from any one battle, or that skirmishes did not last for an extended period of time, or that military projectiles had not yet been invented that would inflict a high degree of injury to numerous people at the same time. Determined thought had not been seriously given to using ambulances, establishing forward dressing stations with rear field hospitals, and using trained personnel to carry the wounded by litters. The enormity of wounded from early Civil War battles changed that long held perspective. Following the battle of 2nd Bull Run or Manassas (August, 1862), it took over a week to remove the wounded from the battlefield.

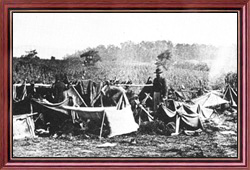

|

| Confederate Field Hospital September 20, 1862 |

Just a month before Antietam, Jonathan Letterman, Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac, devised an efficient system of ambulances and trained stretcher bearers to evacuate the wounded from battle as quickly as possible. This plan was first used at the Battle of Antietam where its implementation was given a full test, because the wounded numbered in the thousands and quickly flooded the newly devised system. Military ambulances, field dressings, and litters were used for the first time by the Union army, but Confederate forces soon developed similar plans. Specially trained stretcher bearers would gather the wounded and transport them to forward dressing stations where bandages and pain medicines were administered. Under the stress of battle, the wounded were then transported by ambulances to rearward hospitals where amputations were common, usually because of the types of ammunition that was designed to produce the most gruesome effects on the human body. It was a nightmare at the field hospitals of Antietam. Soldiers rarely bathed, as forced marches between battles required them to live in sweat-stained clothing that also bore food stains. Poor rations mixed with exhaustion resulted in the prevalence of diarrhea. Suffering for the wounded in their make-shift conditions at Field Hospitals only intensified as incapacitated diarrhetic soldiers could not prevent the misery and humiliation of defecating in their already filth laden clothing. The stench was horrible, compounded by the recurring moans of unrelenting and excruciating pain. Attendants were in short supply, and so was hope of relief. How could any soldier have imagined this scene on the day of his enlistment. Compounding their misery now were the bystanders and the inquisitive who came from nearby towns and farms to investigate the event, for the din of battle naturally creates anxiety and curiosity. People would gather at these field hospitals in order to learn what happened. Wounded men preferring compassion were often subjected to insensitive gawking or meaningless conversation. Once the battlefield was secure, a few would traverse the area looking for souvenirs. Personal items were routinely taken from dead bodies. The battle of Shiloh (April, 1862) yielded the first massive number of casualties, bringing a shocking realization to both sides of the human cost of the war. After two days of fighting, over twenty thousand dead lay strewn across the field. Souvenir hunters combed the area for mementos, stepping over corpses, to gather weapons, cartridges, gun-flints, canes, diaries, knives, and Louisiana pelican buttons. Wounded men lying in field hospitals lost their comrades, only to learn that their bodies had been callously pilfered. Now, the cold-hearted reality of warfare was making its mark on these men, whose suffering frequently became maddening. From the estimated 623,000 soldiers who died in the Civil War, 388,500 died of disease. The effects of infection, diarrhea, pneumonia, and typhoid had taken their toll. Only in their dreams could these wounded soldiers have imagined the compassionate attention of a personal angel.

Clarissa Harlowe Barton was born in Oxford, Massachusetts, on December 25, 1821, the daughter of a horse breeding farmer and a mother that especially stressed personal hygiene and cleanliness. When an elder brother fell from the barn roof, eleven year old Clara played nurse for his nearly two-year convalescence. She also took delight in caring for wounded pets. Following graduation, Barton started a career in teaching but after the death of her mother in 1851, she moved to Washington and served as a copier in the U.S. Patent Office. Here she also began to see matters from the national perspective. Her interest in assisting the military commenced with the arrival of the Sixth Massachusetts Regiment in April, 1861. The regiment’s baggage had been lost, so she initiated efforts to supply them with towels and handkerchiefs made from old sheets.

Following the battle of Bull Run or Manassas, she was grieved by reports of the shortages of battlefield supplies. She advertised in a newspaper for provisions and when sympathetic readers sent enormous amounts of supplies, she then established an agency for distribution. In 1862, she received government permission to accompany sick transports and serve in aiding the wounded. At first, Union officers did not want her around, thinking her presence would be more of a hindrance or distraction, or fearfully both. An independent women exhibiting courage was deemed inappropriate in contemporary thinking. Even though her efforts were noble and appreciated, she was largely considered to be a liability. During the Battle of Cedar Mountain (August, 1861), she assisted at the Culpeper train station which had been converted into a field hospital. The scene was horrid and sickening. Army surgeons amputating limbs in bloodstained coats that reeked with pus and tattered flesh. Battle after battle she would persevere in delivering needed bandages and medicines, and treating the wounded in whatever means possible.

As conflict erupted along the Antietam near Sharpsburg, her wagon followed the Union 2nd Corps, arriving at the northern perimeter of the Miller Cornfield around noon. The spectacle before her eyes was dumbfounding. Insanity had displaced even a remote semblance of normality. Army medical supplies had not yet reached the battlefield and surgeons were actually dressing the wounded with corn husks. Her arrival with a full wagon load of bandages and medicines was met with supreme gratitude by harried surgeons and their staff. Undaunted by whizzing bullets and the percussion of artillery, Clara Barton set about helping the fallen in any way possible. She distributed medical supplies, prepared food, carried water, and cradled their heads when needed. The story is told that as she gave a drink of water to one man, a bullet pierced her puffed sleeve and upon glancing to inspect what may possibly have brushed against her sleeve, her eyes returned to discover that the bullet had killed the very man whom she was assisting. She worked tirelessly until nightfall. In the twilight, she could be seen in her bonnet and dark skirt, gliding across the battlefield from one concern to another. It seemed as if God had sent a special angel to administer grace to the helpless. Without thought of riches or poverty, ethnicity or culture, this Angel persistently glided from soldier to soldier, attending as many suffering cries as she was able. Even darkness would not deter her efforts for she also produced lanterns from her wagon to assist the surgeons in their work. The next day she assisted at the Poffenberger Farm in the North Woods where she delightfully renewed the acquaintance of Doctor James L. Dunn, a surgeon with whom she had met at the Culpeper railroad station turned field hospital (Battle of Cedar Mountain). Hardened now from constantly witnessing the arena of blood, knives, saws, and hasten medical procedures, Barton was undeterred by the ghastly scenes of the field hospital that had sickened her months before. So keen was her observance of surgical procedures, that she was even allowed to perform some minor surgery on less distressed cases. This naturally augmented her self-esteem, a modest reward for her grueling months of dutiful labor. Noticing her compassionate yet tenacious attitude, Mrs. Dunn called her: “the true heroine of the age, the angel of the battlefield.”

All this came at a price for Barton later collapsed and was transported to Washington, suffering from exhaustion and a bit of typhoid. Following the Civil War, she worked for several years at her usual tireless pace to help identify unknown dead soldiers, coinciding with other efforts to relocate and memorialize the fallen. Hastily created battlefield cemeteries were excavated and remains were either deposited in specially dedicated military cemeteries or relocated to private family graveyards. Working under the direction of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, she and assistants went to the infamous Andersonville prison camp in Georgia to identify soldiers in unmarked graves. Over the next four years with the help of many volunteers, Barton successfully identified thousands of dead from many Civil War battlefields, gaining her national recognition. She also became the first woman to head a government bureau: “The Missing Soldier’s Office.”

While traveling in Europe in 1870, Barton volunteered her energies to the International Red Cross, and was assigned to service in the Franco-Prussian War. She was impressed with the difference in organization which permitted more efficient processing of work than had been possible during the Civil War. She became good friends with the Grand Duchess Louise, daughter of Kaiser Wilhelm. In recognition of her indefatigable spirit, Barton became the only women to have been awarded the Iron Cross. After returning to the United States, the International Red Cross invited her, in 1877, to establish an American chapter and she lobbied to gain financial support, and increase national awareness through the publication of brochures and personal speeches. On May 21, 1881, the American Association of the Red Cross (later American Red Cross) was founded. Realizing that people also suffer greatly during peacetime, Barton soon expanded the mission to also include victims of natural disasters, such as hurricanes, fires, earthquakes, and floods. Her vision and persistence also contributed to the United States ratifying the Geneva Convention in 1882. Many grateful people will always remember her as the “Angel of the Battlefield” who ministered to stricken soldiers at Antietam, not far from that Little Dunker Church.

Civil War photographs still tell their stories in the modern world by satiating our unfettered inquisitiveness about the past. Often it is the photograph alone which impacts us with the horridness of war, eclipsing even the vivid force of the printed word. Faces of the living in period dress give us a strange feeling of wonderment and the faces of dead soldiers evoke a repulsive captivation. Although men had experimented for years with capturing images using various light sensitive chemical substances, it was the French opera scenery painter, Louis Jacques Mand矄aguerre, who invented the first practical process which he named after himself, the daguerreotype. His forerunners captured images only after hours of exposure, a hopelessly impractical method, even in the studio. After years of experimentation in partnership with Joseph Nic诨ore Ni诣e, he was able to develop a direct positive image on a silver-coated plate (not a negative). This process gained popularity quickly and by the 1850’s, there were over seventy daguerreotype studios in the city of New York. Another type of photographic process that would be developed by the time of the Civil War was the wet glass plate negative, used by professionals such as Matthew Brady, Alexander Gardner, James Gibson, H.T. Anthony, and George S. Cook. Working to advance the science of photography beyond the work of Daguerre and Ni诣e, Frederick Scott Archer experimented with collodion to hold light-sensitive salts to glass plates, producing the first glass photographic negative in 1848. Two years later, Archer donated this process into the public domain. Although claim to be the first combat photographer would rightfully go to Cook for his images at Fort Sumter, and the prize for capturing some of the earliest Civil War battlefield images to Gibson, it would be Matthew Brady who would become the most well known of all Civil War photographers. His name is even synonymous with the words Civil War. Through his New York Gallery at the corner of Broadway and 10th, Brady revealed the horridness of war to the commoner and the elite. The New York Times expressed these words on October 20, 1862:

“The living that throng Broadway care little perhaps for the Dead at Antietam, but we fancy they would jostle less carelessly down the great thoroughfare, saunter less at their ease, were a few dripping bodies, fresh from the field, laid along the pavement. There would be a gathering up of skirts and a careful picking of way ... Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along streets, he has done something very like it ... We should scarce choose to be in the gallery, when one of the women bending over them should recognize a husband, a son, or a brother in the still, lifeless lines of bodies, that lie ready for the gaping trenches ... Homes have been made desolate, and the light of life in thousands of hearts has been quenched forever. All of this desolation, imagination must paint for broken hearts cannot be photographed.”

Matthew Brady’s eyesight began to deteriorate in the 1850’s and he gradually began to delegate more responsibility to his staff. As the years passed, most of the camera work, both in the studio and the field was done by subordinates. He would line up or compose the shots, apply cosmetics as needed, and advise the use of costumes. Alexander Gardner joined him in 1856 and their enterprise became very successful. Gardner’s excellent mastery of wet plate processing resulted in the production of over 30,000 portraits a year. They photographed Abraham Lincoln as a Presidential candidate, to which Lincoln later remarked: “It was Brady’s picture and the Cooper Union speech that made me president.” Some of the best known photos of Lincoln were done by Brady and Gardner, including the profile on the Lincoln penny. Matthew Brady was the most influential photographer of the 19th Century. However, it was Alexander Gardner who took all of the photographs on the Antietam battlefield.

Alexander Gardner |

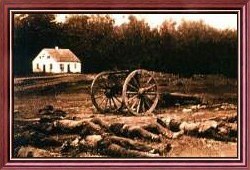

Alexander Gardner was born in Scotland in October, 1821, and left school at the age of fourteen to become an apprentice jeweler. He was particularly impressed with Matthew Brady’s photographs at the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, London, in 1851. This peaked his renewed interested in an adolescent fascination with chemistry and he began experimenting in both the art and science of photography. Upon moving his family to America in 1856, he gained employment in the Brady studio in New York City. In a short period of time, he became an expert at the wet plate process. Gardner was put in charge of Brady’s Washington, DC, gallery in 1858, and gradually acquired notoriety as the premier portrait photographer. After the assassination of President Lincoln, it was Gardner that photographed each alleged conspirator, and following their convictions he photographed their group execution by hanging in the prison yard of the Washington Penitentiary in 1865. Brady invested his life savings in a decision to make a pictorial collection of the Civil War in the hope of making a fortune from the residual interest that was most likely to continue for years. He dispatched Gardner and several other associates to travel around the country and capture the war on film. They were to record the sensational and the humdrum. Gardner soon found a ready market in soldiers who wanted to be photographed before going into combat. He made a large number of portrait images of men from different ranks. Some historical figures are recognized only by their Gardner photograph. Modern educational textbooks use many of Gardner’s photographs to accompany their historical narratives. In November, 1861, Gardner was assigned to the staff of General George McClellan, and even granted the honorary rank of Captain. It was Alexander Gardner and his assistant James Gibson who photographed Antietam. It is through their eyes that we view the repulsive captivation of dead bodies lying in Open Fields, next to Roads Ways, in the Sunken Road, and before the Little Dunker Church. These seasoned craftsmen had nearly four days to move their wagon around the battlefield and record everything from the dead in the West Woods to the living in the village of Sharpsburg.

It has not been clearly determined at what time Gardner and Gibson reached the battlefield, possibly on the same day of the battle and towards evening, or more likely the next morning, September 18. But it was not until September 19 when it was certain that the Confederate army had withdrawn, that Gardner plunged into the task before him with complete freedom of movement. Even though he had several days to record the images, Dead Bodies were naturally being gathered and buried all the while, thus even his own photographs do not exhibit the battle’s full impact. In the Sunken Road later called Bloody Lane, one can see that most bodies had already been cleared from the left or southeastern portion. Immediately after the shooting had ended in the evening of September 17, this and many other scenes would most probably have been much worse. From Gardner’s own captions, it would appear that he and Gibson started in the northern area where they captured images in the West Woods along the Hagerstown Pike, and then in front of the Dunker Church. Over the next two days, they apparently moved south through Bloody Lane and then to Burnside Bridge, after which they transported their equipment into Sharpsburg, near to where McClellan had established a second headquarters. They photographed Streets, Buildings, and Churches. Gardner and Gibson made ninety-five negatives at Antietam during September and then later in October when President Lincoln visited the battlefield to review the military situation. It was Gardner who took the now famous photograph of Lincoln and the soon-to-be-fired McClellan inside the General’s tent, which some have humorously titled: “Friend or Foe.”

More attention was given by newspapers and magazines of the time to the photographs of Antietam than any other photographic series of the entire four years of war, including Gettysburg. One reason being that Antietam was the first battlefield in the history of American warfare where cameramen were able to capture photographs of the dead before they could be buried. Unfortunately, the residual market for Civil War photographs did not materialize. Matthew Brady later declared bankruptcy and finally became an alcoholic. Some historians suggest that interest in such photographs subsided largely because people just wanted to put the conflict behind them, and continue with rebuilding their lives and the nation.

Alexander Gardner supervised Matthew Brady’s Washington, D.C. gallery from 1858 until 1863, when he established his own gallery. He took the Antietam negatives with him and most of the Brady staff who preferred to defect. Gardner was later commissioned as the Union Pacific Railroad chief photographer to document the investigations of the survey team proposing to extend the rail line along the 35th Parallel. Gardner later wrote about his experience on the Antietam battlefield,which included these words: “Let them aid in preventing such another calamity falling upon the nation.”

The number of casualties in the Battle of Antietam are much less than the three day campaign at Gettysburg which claimed an estimated fifty-one thousand lives, but this battle near Sharpsburg, Maryland, holds the record for the greatest number killed, wounded, or missing from ONE DAY of fighting. Exact totals for each phase are difficult to calculate because some records contradict each other. The following are taken from the National Park Service.

| PHASE | UNION | CONFEDERATE |

Morning |

||

| Cornfield | 4,350 | 4,200 |

| West Woods (Dunker Church) |

2,200 | 1,850 |

| Mid-Day | ||

| Sunken Road | 2,900 | 2,600 |

| Afternoon | ||

| Burnside Bridge | 500 | 120 |

| Final Attack | 1,850 | 1,000 |

| Missing/Captured | 750 _______ |

1,020 _______ |

| Totals | 12,550 | 10,790 |

| Above statistics from National Park Service.

See also US Department of Defense or US Department of Veterans Affairs. See also Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Civil War: 4,710 dead, 18,440 wounded, 3,043 missing for a total of 26,193. |

Photo Credits:

All modern photographs by Ronald J. Gordon © 1998, 2002. Other photographs, images, or reproductions are displayed with respect to intellectual property and compliance to all known Copyrights.

Bibliography:

A complete listing of all resource materials involved in the production of this resource can be found at the bottom of the home document. Included are hard print literature, numerous maps, graphic images, and links to related web sites. Unlisted are numerous trips to the battlefield, visits to associated congregations, and personal interviews.