Written by Ronald J. Gordon Published: August, 1998 ~ Last Updated: March, 2013 ©

This document may be reproduced for non-profit or educational purposes only, with the

provisions that this document remain intact and full acknowledgement be given to the author.

|

|

Dunker is a moniker for a people of faith that originated in 1708 near the village of Schwarzenau, Germany, along the Eder River. Originally, calling themselves Neue Taufer (New Baptists) in order to better distinguish themselves from older Anabaptist groups, such as the Mennonites and the Amish. We use the label Schwarzenau Brethren to designate this original body, since there have been a number of Brethren Groups that formed through splits and sub-movements over the centuries. Typical of the derisive labeling experience of many religious groups, they were called Dunkers by outsiders because they fully immersed or “dunked” their baptismal candidates in nearby streams, three complete dunkings; a particular method of baptism that completely distinguished them from the “sprinkling” Lutherans and Methodists, their kindred “pouring” Mennonites, and even the single dunk Baptists. For this reason, numerous Brethren congregations are still known by the body of water where these baptisms or dunkings took place: Beaver Creek, Yellow Creek, Lost Creek, Marsh Creek, Pike Run, Spring Run, Trout Run, Blue River, Eel River, West Eel River, Little River, Valley River, Falling Springs, Roaring Springs, or Three Springs. Brethren stem from German Pietism (a religion of the heart) of the Eighteenth century and the Anabaptist (re-baptizers) movement of a previous century. This latter movement sought to reform the European State-Church system by emphasizing the process of regeneration whereby adult believers accept entrance into the faith through a mature decision, that stresses personal awareness of eternal consequences and the enlightened understanding that Christ is the answer to the problem of human sinfulness.

Members of this Brethren sect later emigrated to America between 1719 and 1733, during a period when religious intolerance in Europe began to increase. They established many settlements and congregations throughout Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas. Presently, there are seven denominations that trace themselves back to this original group from Schwarzenau, Germany: Church of the Brethren, The Brethren Church, Fellowship of Grace Brethren Churches, Conservative Grace Brethren Church International, Dunkard Brethren, Old German Baptist Brethren, and the Old Order German Baptist Brethren. The largest group is the Church of the Brethren with one seminary and six affiliated colleges.

Brethren settled early throughout most of eastern and southern Pennsylvania, establishing large congregations which later gave birth to smaller daughter groups. Nestled in the southeastern part of the large Cumberland Valley, the Antietam Brethren were originally a mission project of the Eastern Pennsylvania congregations. This was a large valley, at some points nearly thirty-five miles wide and over fifty miles long, extending from the Susquehanna River to the east and then curving south to the Potomac River in the west, and bordered its full length by the Blue Mountains to the north. Brethren referred to this area as their Conococheague District (pronounced: kon no kaa JIG) because of the Creek by the same name which flowed through its mid-section. Also rippling through this valley was the Antietam Creek, a southward flowing stream which starts near Waynesboro, Pennsylvania, and empties into the Potomac south of Hagerstown, Maryland. The battlefield church (Mumma) is located near this same stream, though many miles to the south. Brethren leader Jacob Price, newly arrived from Philadelphia, assisted this loose-knit group of Brethren to formally organize into a Congregation in 1752. For this reason, many people also call it the Price Meeting House. Over the years, many other leaders would come to hold revival meetings or otherwise contribute to its growth and spiritual firmness. Services were held in homes until the first meeting house, a building of native stone, was constructed in 1795. The present brick building of the Antietam Congregation was erected in 1892. Initially, Antietam was an extremely large congregation with hundreds and hundreds of members, stretching over vast territory in south-central Pennsylvania and north-central Maryland. Gradually, these Brethren sub-divided into many smaller Daughter Congregations: Manor -MD (1800), Welsh Run -PA (1810), Ridge -PA (1836), Back Creek -PA (1850), Beaver Creek -MD (1858), Falling Springs -PA (1866), Hagerstown -MD (1893), Chambersburg -PA (1910), Waynesboro -PA (1922), Shippensburg -PA (1924), Broadfording -MD (1924), Long Meadows -MD (1926), Greencastle -PA (1930), Welty -PA (1934), and Rouserville -PA (1949). Of particular interest to us is the Manor Congregation (1800) near Hagerstown, which was also joined by Brethren moving east from Frederick County, Maryland. The original gray limestone rock church built in 1839 is still in use. Dunkers populated the region and the Brethren message of non-violence and spiritual regeneration flourished. Manor steadily gained prominence among the young denomination, for they twice hosted the denomination’s Annual Conference, in 1838 and again in 1857. As the influence and spiritual strength of this congregation grew, a strong contingent of ministers emerged that would start daughter congregations in the immediate area.

|

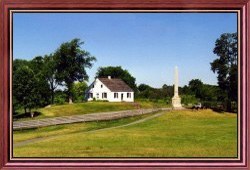

| Mumma Farm |

In 1852, the third congregation to be daughtered from Manor built a church (then called meeting houses) next to the Hagerstown Pike ( Route 65 ) on land donated by Brethren farmers Samuel and Elizabeth Mumma, whose land extended from the Pike on the west toward the Antietam Creek to the east. Original member families were Mumma, Ecker, Sherrick, Miller, and Neikirk. This is the now famous battlefield Dunker Church that fell victim to morning artillery and rifle fire from Union and Confederate troops on September 17, 1862. Ironically, only ten years after it was founded, the meeting house of this Pacifist congregation was nearly destroyed by the very thing that it protested, bombed by the very artillery shells that it sought to deter, and stained by the blood of men that should not have suffered. The Mumma’s (pronounced MOO’ maw) were zealous members of the Dunker or Brethren faith. Their large farm was prosperous and contained a generously Large Cemetery that included many graves of their relatives and neighbors. Land records of Washington County show the following preamble to the new church deed which attests to their profession of faith. This church still stands as a testimony of their faith and their desire to prevent the very degree of carnage that it witnessed.

"This Indenture made this twenty-second day of February in the year of our Lord eighteen hundred and fifty-one between Samuel Mumma and Elizabeth Mumma his wife of Washington County in the State of Maryland of the one part, and Joseph Wolf, John S. Rowland, Samuel Fahrney, Jacob Reichard, Samuel Emmert, John W. Stouffer, and Valentine Reichard, deacons of the church who call themselves Brethren, having and considered the Holy Scriptures alone as the object of their faith; and holding and professing only the New Testament solely as the rule for their church government and for their religious practices, renouncing and disowning all other creeds, men’s confessions of faith and elders’ tradition, preferring and professing the deciding, determining, and squaring all Church matters by and with the New Testament."

History of the Church of the Brethren in Maryland by J. Maurice Henry, 1936.

|

| Mumma Church Built 1852 |

Samuel and Elizabeth Mumma were a stable Brethren couple and very instrumental in establishing the newly formed congregation, explaining why the soon to be erected house of worship would be called the Mumma Meetinghouse or the Mumma Church. The Brethren never yet actually having a denominational name for uncertain reasons, a label of some kind became a growing necessity during the early 1800’s because of property transfers and other legal documentation. In 1836, many Dunkers appended the word Brethren to the contemporarily used label German Baptist, to become the German Baptist Brethren, a label that was not officially sanctioned by Annual Conference until 1871. Predictably resisting change, some daughter congregations from Manor continued to use only German Baptist, but the Mumma flock decided to append the word Brethren to keep in step with the most of the denomination. Work began on the new church in 1852 and finished the next year. Bricks were baked from clay in an earthen kiln on the John Otto farm. Predictably, the new congregation adopted the non-violent stance of the denomination and further required new members to promise “never to own slaves or engage in war.” The church was small and plain, just like the plain Dunker people who built it. No steeple adorned its entrance because the Dunkers considered them immodest or worldly. Services of worship convened each Sunday morning with men entering the door facing toward the Hagerstown Pike (front) with women and children entering through another door in the south wall (left). This was in keeping with the trend of Brethren congregations whose meeting houses were usually segregated by gender. Plain and functional captures the Inside Appearance of the Mumma Church. Austere wooden benches provided seating around a central stove. Ceilings and walls lacked decoration. Ministers typically did not use a pulpit but instead lay their effects on a Long Table that was located at the front of the church. A large Bible prominently lay on this table along with a glass and pitcher of water. It is called the Pulpit Bible by most people today even though the early Brethren did not use pulpits, an assumptive matter of historical intrusion by other denominations. Behind the Long Table, a presiding Elder and his coterie of ministers sat on a single bench, each taking their respective turn at Preaching.

Furnishings and practices varied among Brethren congregations with some having three and sometimes four sermons over the morning, because this was a period when Brethren generally did not observe Sunday School. Dunkers felt that biblical instruction for children was a duty of parents in the home, and Sunday morning was the time for those parents to receive their own spiritual guidance. Interestingly enough, the matter of instituting Sunday School was voiced at the denominational Annual Conference on two occasions, and both times it was held at the Manor Congregation. In 1838, the Brethren voted against Sunday School and in 1857 they formally adopted the practice. In another fifty years, the issue would be moot because of its wide acceptance by many congregations. Brethren were plain people in lifestyle and dress. They were purposely reserved in accepting innovation or change, and their buildings matched their beliefs. So unostentatious was the outside appearance of the Mumma Church, that Union officers looking from the North Woods on that early Wednesday morning thought it to be a School House.

The original Schwarzenau Brethren, organized in 1708, were heavily influenced by German Pietism and Anabaptism of more than a century before. Their emergence from a small district in Germany is not unrelated to the historical circumstances surrounding that period, being a war ravaged, economically impoverished landscape that was brutally contested for by Protestants and Catholics. Farms and crops were over-run and destroyed by armies so frequently that farmers became discouraged to plant their grain seed, and this later created devastating food shortages.

Pietism

A spiritual flower of hope was seen by many religious refugees in Pietism, a religion of the heart that disdained the formalism and sacramentalism of the big tree State-Churches: Catholic, Lutheran, and Reformed. Most of the early Brethren came from a Reformed background, having cut their teeth on the Heidelberg Catechism. Originally content to remain as a sub-group within the Big Three state churches, Pietists endeavored to substitute devotional formalism with a more genuine intellectual and emotional experience. Adherents stressed that faith, regeneration, and sanctification were qualities to be experienced rather than being explained by church officials. Local governments, overwhelmed with administrative disruptions and economic recovery from years of war, took little notice of Pietism in its earliest form. However, when the more radical Separatists evolved, that would all change, for this new sub-group desired to clearly take the movement outside of the Big Three, and possibly exist as free independent groups without denominational structure. Pietism was birthed in Germany through spiritual pioneers who wanted a deeper emotional experience rather than rote adherence to form. They stressed a personal experience of salvation and a continuous openness to new spiritual illumination. They also taught that personal holiness (piety), spiritual maturity, Bible study, and prayer were essential towards “feeling the effects” of grace. Many early Pietists were content to remain in established churches, but in the late 1600’s awakened souls risked the danger of separating from all state churches, and these Separatists were branded as radicals and fanatics, if not outright heretics. Many were severely persecuted, imprisoned or executed for simply going too far. These more radical groups went beyond the Anabaptist focus on mere conduct reflecting saving grace, because they stressed the need to personally “sense” the effects of grace. Separatists, Awakened Souls, or New Reformers became intent on awaking everyone else from the complacency of mechanical religiosity with its grand but empty pageantry.

Anabaptism

Radical Separatist philosophy mixed well with Anabaptism, the latter being a theological and academic reaction to the monolithic State-Church system. Because of its open challenge to both church and secular government, it has been improperly viewed as a political movement. Born in Switzerland in January of 1525, toleration for this fledgling movement came first in the Netherlands where the Catholic priest Menno Simons had already renounced his allegiance to Rome. Other havens gradually appeared when nobility realized that most Anabaptists were hard working farmers and craftsmen who quickly contributed to their local economy. Following the Thirty Year’s War that left feudal economies in ruin, many such groups were actually invited to settle in the Palatinate district of Germany, in order to rebuild the war stricken landscape. Hutterites also found refuge farther east in Moravia. Numerous attempts were made to formally record a basic consensus of Anabaptism by its followers. The most notable are the Schleitheim Confession of 1527, named after the Swiss-Austrian border city where early leaders secretly met, and the 1632 Dutch Mennonite Dordrecht Confession which is principally followed by many Amish. Intellectual disagreement remains over the full effect of Anabaptism on the Schwarzenau Brethren, however, a clear imprint of these early convictions is most visible as the Original Eight souls initiated their faith community through the rebaptism of each other as believing adults in the Eder River near Schwarzenau.

Modern groups stemming from Anabaptism rarely perform rebaptisms because their children are not first baptized as infants. Youth generally receive baptism and membership when they reach that varying age of truly understanding and accepting the gospel message centered in the teachings of Christ. Anabaptists in the modern era are known for their distinctive beliefs and cultural heritage. With little variance, they stress very closely the same doctrinal positions as their 16th Century advocates, such as, but not limited to:

- Priesthood of all believers

- Separation of Church and State, with laws of God taking precedence

- Voluntary membership in the Church, unregulated by the State

- Baptism as a sign of a believer’s commitment

- Discipleship being central to understanding the teachings of Jesus Christ

- Non-violence and Non-resistance

- Refusal to bear weapons or engage in military service

- Separation from sinful and worldly pleasures

Brethren were a plain people, in dress and practice. Clothing lacked special decorations. Buttons and jewelry were noticeably missing. Men wore beards and usually without mustaches, a carry over from their European period when broad mustaches were the pride of Calvary officers. Dark suits and broad brimmed hats were common for men. White caps covered the hair of women along with unstylish dresses, often with caped-fronts. This plain clothing was often called The Garb.

Peace & Non-Violence

Non-violence and Non-resistance were integral hallmarks of Anabaptism and this stance was costly for Europeans during the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries. Brethren or Dunkers adopted non-violence as one of their core beliefs. Many suffered complete loss of land and personal wealth because of the incorrect political suspicions that accompanied the Brethren. German printer Christopher Sauer II, a member of the original Germantown congregation of newly arriving Brethren In America, lost everything and was treated with humiliation for his beliefs. “If a person wasn’t good enough to fight for their country, what good are they?” was a phrase leveled at them most often. Remarks such as these miss the central issue of non-violence for they reveal a presumption on the part of the antagonist that pacifists are not patriotic - a demonstrably improper conclusion. Brethren Elder John Kline was murdered while riding horseback because he regularly preached to Dunkers on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line, and therefore regarded by some as a traitor and a spy as well. Brethren are very patriotic but seek to donate their life fruit through service to both God and country.

Dunkers believe intently that their lives are to closely align with the teachings of Jesus Christ as found in the New Testament, their primary source for developing rules of faith and practice. It is difficult to find a New Testament basis for the killing of another human being since Christ taught: “Ye have heard that it hath been said, Thou shalt love thy neighbour, and hate thine enemy. But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you; That ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven: for he maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust. For if ye love them which love you, what reward have ye? do not even the publicans the same?” - Matthew 5:43-46. Adversaries of pacifism often charge that Jesus was not a pacifist. In response, the Dunkers counter that Christ lived by His own teachings on pacifism. There is no record of Jesus killing anyone. There is no instance of Jesus suggesting that believers should kill anyone. Instead, Jesus prayed for those who persecuted Him, mourned for the city of Jerusalem when it did not recognize its opportune moment, and forgave the very soldiers who nailed Him to a cross. Non-pacifists usually revert to non-scriptural methods involving logic, reason, or theory to establish their claims. Pacifism looks upon violent behavior and pleads with it to spiritually and intellectually rise above it to a higher Kingdom.

Slavery

What did the Dunkers believe concerning slavery, at the official denominational level? Since the Dunkers or Brethren had migrated from Pennsylvania into a few southern States (Maryland, Virginia) with significant slave populations, the issue of slavery would inevitably confront them denominationally at their Annual Conference. The earliest record of an official mention was in their Annual Conference minutes for 1797, held at Blackwater, Virginia: “It was considered good, and also concluded unanimously, that no brother or sister should have negroes as slaves; and in case a brother or sister had such he or she was to set them free.” [1] This had the effect of barring members from Communion and even disfellowshipping those who persisted in retaining slaves. Again the issue was similarly reflected in the minutes of the 1713 Conference held at Coventry, Pennsylvania.

But how did the Dunkers feel about having slaves or negroes in full membership status? The first mention is found in the 1835 Conference minutes from Cumberland County, Pennsylvania: “It is considered, that inasmuch as the gospel is to be preached to all nations and races, and if they come as repentant sinners, believing in the gospel of Jesus Christ, and apply for baptism, we could not confidently refuse them.” [2]

Should members “hire” slaves from slaveholders, thus evading any ruling concerning ownership while still enjoying the benefits of their labor? It was a very common practice in slave States for people to hire slaves from their masters under a contractual agreement: so many slaves, for so much work, for such a period of time. Questions regarding slavery or related matters repeatedly came to the Dunker or Brethren Annual Conference for consideration, but one of the more definitive pronouncements is found in the minutes of the 1855 Conference held at Linville Creek, Virginia: “We, the Brethren of Augusta, Upper and Lower Rockingham, Shenandoah, and Hardy counties having in general council meeting assembled at the church on Linville Creek; and having under consideration the following questions concerning those Brethren holding slaves at this time and who have not complied with the requisition of Annual Meeting of 1854, conclude: That they make speedy preparation to liberate them either by emancipation or by will, that this evil may be banished from among us, as we look upon slavery as dangerous to be tolerated in the church; it is tending to create disunion in the Brotherhood, and is a great injury to the cause of Christ and the progress of the church. So unitedly we exhort our brethren humbly, yet earnestly and lovingly, to clear themselves of slavery, and that they may not fail and come short of the glory of God, at the great and notable day of the Lord. Furthermore, concerning Brethren who hire a slave or slaves, and paying wages to their owners, we do not approve of it. The same is attended with evil which is combined with slavery. It is taking hold of the same evil which we cannot encourage, and should be banished and put from among us, and cannot be tolerated in the church.” [3]

Long before cannons sounded in Charleston harbor, the Dunkers repeatedly gave clear and unambiguous official statements regarding their beliefs over the issue of slavery. It was an “evil” that could not be “tolerated in the church” because the “gospel of Jesus Christ was to be preached in all nations to all races.”

1. Freeman Ankrum, SIDELIGHTS OF BRETHREN HISTORY, Elgin: Brethren Press, 1962, p. 91.

2. Ibid. p. 92.

3. Ibid. p. 93-94.

One of the unnoticed tragedies for most visitors to this battlefield is that most of the fighting took place on ground owned by a biblical people that did not believe in killing - the Dunkers. September 14, 1862, was probably no different than any other Sunday morning gathering of the Mumma Dunkers. The pulpit Bible was read by Elder David Long, age 42, hymns would be sung, and preaching would be long in the gleaming white wall church along the Hagerstown Pike. It would delight the student of history to know what scriptures were actually read that morning and what the sermons were about, for simultaneously, General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and Union General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac were preparing for battle. They would soon converge on this elongated ridge and the bloodiest day of battle in our nation’s history would erupt just outside the gleaming white plaster walls of this church of peace. By noon, its frame would be scarred and the inside Heavily Damaged. In the very place where men and women sang the praises of God, the tortured cries of men writhing in agony would be all too clear. Joy would be replaced with misery and wooden benches garnished with blood. Along the very paths where families had walked to this Dunker Church, soldiers would soon die as they fought to claim its high ground. Over 8,500 casualties would be listed in David Miller’s Cornfield that lay diagonally across the Pike and another 4,000 in the West Woods behind and north of the Dunker Church. More than twelve thousand men would be casualties in just a few morning hours in the general proximity of this church of peace. But this was only the morning phase. 5,500 more casualties would be listed in the Sunken Road or Bloody Lane and over 3,000 near the Burnside Bridge during the late afternoon phase when Union forces tried to cross Antietam Creek toward the Confederate right flank, and a final attack of nearly 2,000. In total, around twenty-three thousand troops would be killed, wounded, or missing in less than twelve hours of fighting, or nearly one every two seconds.

|

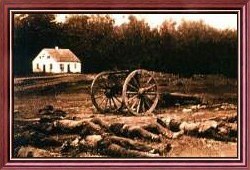

| Mumma Farm Burned 1862 |

The Dunker Church would not be the only Dunker property that would fall victim to the machinations of battle this day, for Confederate soldiers would burn the Mumma farm to the ground, in order to prevent Union sharpshooters from gaining an advantage from its Strategic Position. Sunday evening, the children while playing in the fields saw smoke rising from the gaps of South Mountain and ran back to their farm with reports of what they had seen. Samuel Mumma and visiting friends went to the barn and watched Confederate infantry trying to retain control of all three passes across South Mountain from the Union army that was advancing west from Frederick. By late evening, Union forces had taken each pass and the Confederate army fell back across Antietam Creek and quickly entrenched themselves on the top of a ridge that stretched north from Sharpsburg and parallel to the Hagerstown Pike. Early the next morning, the Mumma family saw Confederate soldiers on nearly every side. Neighbors and church members gathered at their farm in order to decide the best course of action. Finally, they decided to seek protection at the Manor Congregation. First, the children were escorted while the adults made several last minute decisions. It was a long northerly walk, passing Confederate soldiers everywhere. Never had they imagined the overwhelming numbers of men, horses, and weaponry that would saturate their homeland. Troops. Wagons. Limbers. Cannons. Flags. Generals. Rifles. Drums. Bugles. So many elements of destruction. Only this past Sunday, the children had walked these very roads on their way to that Little Dunker Church where love and peace was instilled in them. How ironic! A peaceful people overtaken by the very human propensity for destruction, against which they have historically witnessed. How also could they know that this day would be the bloodiest day of battle in United States history? All, to occur before their little Dunker Church.

Earlier this morning, before daylight, Samuel had sent away his son with the horses for safe keeping because invading armies routinely stole horses. When Lee invaded Pennsylvania the next year (1863), many farmers had their horses removed for safe keeping to a valley north of Carlisle, Pennsylvania, that is still called Horse Valley to this day. As two Mumma daughters fled to relatives, the story is told that soldiers offered to help them climb over a fence, to which they replied: “No, you shall not help us. You are driving us from our home!” Late Monday evening, most of the adults had begun their long walk to Manor. Who can know the sense of distress and uncertainty that must have dominated their minds. Perhaps they rejoiced that God had seen fit to spare their lives, and yet they bemoaned the unfairness of war, especially for a community of peaceful believers that stressed the need to resolve conflicts through non-violent means. Thus, the quintessential moment when God is unfairly blamed for everything by unbelievers. People of faith understand that it is God who helps us “through” the calamities of life. God did not spare Noah’s farm from the Flood but preserved his family “above” it. God did not spare His people from wandering in the Wilderness but brought them “through” it. God did not spare the three Hebrew children from the fiery furnace but protected them while “in it”. God did not spare His own Son from the cross but gave Him eternal victory “because” of it. Paul the great Apostle of God, giant of faith and to tribulation said it this way: “We glory in tribulations also, knowing that tribulation worketh patience: and patience, experience; and experience, hope.” - Romans 5:3-4.

|

| Dunker Monument to Peace |

Tuesday was mostly a day of strategic troop placements, interspersed with brief skirmishes. During the afternoon, Union soldiers crossed Antietam Creek and dug in for the battle which each side fully expected to erupt at dawn with the predictable barrages of artillery fire. Something else would also erupt, the only civilian property that was intentionally destroyed. In an attempt to thwart the opportunity of Union sharpshooters gaining any advantage from its Strategic Position, the Mumma farm buildings would be set on fire by Confederate soldiers and burned to the ground. Only the white Spring House escaped complete destruction, and it still remains for the modern visitor. Warfare evokes the most horrid dimensions of the mind, the willfulness to kill and destroy and soldiers are keenly trained to overcome their innate apprehensions or reservations. This is accomplished while marching on parade grounds and concentration in shooting ranges. Here is where the soldier overcomes his fear of killing. He is told that the first kills will be difficult but thereafter, routine - just bodies falling down. The Union government later compensated residents for the destruction of their property, but Samuel and Elizabeth Mumma did not receive anything, because it was ruled that their loss was due to actions of the Confederacy. That winter of 1862-63, the Mumma’s would board with their fellow Dunker friends, the Sherrick family. Next year they would rebuild the farm, and their lives.

|

| Pulpit Bible Visitor Center |

Laying on the Long Table at the front of the Little Dunker Church was a large leather bound Bible, 11 x 9 x 2½ inches in size with English text, an 1851 donation from the Daniel Miller family. It is called the Pulpit Bible by most people today even though the early Brethren did not use pulpits, an assumptive matter of historical intrusion by other denominations. It rested instead on the Long Table because these plain people eschewed the stylistic worldliness of pulpits. For literary consistency, we shall defer to calling it the Pulpit Bible instead of the Table Bible. David Long the presiding Elder regularly thumbed its pages. The other ministers stood before it to preach sermons of love, discipleship, separation from worldliness, believer’s baptism, and refusal to bear weapons, or engage in military service. Non-violent resolutions to societal conflicts were expounded by a chain of bearded plain-clothes ministers who stood behind this table. This Bible was the spiritual focus of the Mumma Dunkers. It was opened that Sunday morning before the battle (September 14th) while the Brethren walked along well trodden pathways to the chorus of songbirds, all cast against a colorful backdrop of autumn splendor. The Bible lay in silence as the battle raged all around it that Wednesday morning. It voiced a silent opinion when the Mumma Farm was burned to the ground. Its message of peace was overshadowed by the roar of cannon fire, as wounded men were laid before it throughout the day. Human blood stained the wooden benches in front of it while it told the story of Christ who died on a blood stained cross for sins. Peace was never more close to them.

Following the battle, the empty, heavily damaged church gave a prolonged testimony to the massive destruction of the battle, the Bible all the while remaining on the Long Table. On the morning of the 18th, Corporal Nathan Dykeman of the 107th Regiment, Company H, New York Volunteers, entered the church after walking through the East Woods, and for reasons unknown, picked up the Bible and took it with him. It eventually reached his home in Schuyler County, New York, and there it remained until his death. Did its message of peace speak to his family? Did it have an opportunity to again speak the gospel message of regeneration from sin through spiritual transformation? Did it have the opportunity to inform anyone concerning the peace of God? Was it merely a wartime relic?

Inherited by his sister who first decided to finally return it to the Little Dunker Church, instead sold it to Dykeman’s regiment as a reminder or keepsake. After considerable discussion of the matter by the few remaining members of the regiment, it was decided to return it to the Dunker church from where it had been taken. But how could this be accomplished? Most of these elderly war veterans were advanced in years and a trip of several hundred miles to Sharpsburg would be formidable. There were no Dunkers in upper New York, for this state did not seem to attract the Brethren. However, it was discovered that at least one Brethren man lived in this region, John T. Lewis, an African American who formerly lived in Maryland. Lewis was asked if he would be willing and able to return the Bible to the Little Dunker Church. Indeed, he agreed, and the Bible was returned to pastor Rev. John E. Otto - 41 years, 2 months, and 6 days after it was taken.

|

| John Lewis & Mark Twain |

There is more to this restoration story than just the name John T. Lewis, for he was also a very good friend of Samuel L. Clemens (Mark Twain) and the very person whom Clemens had used to create the personality of Jim, the run-away slave in his novel Huckleberry Finn. Often cited as Twain’s best novel, it is a monumental classic of humor and friendship that powerfully overshadows its racist injections of that period. Huckleberry Finn is a young boy caught between an overbearing widow and a drunken father who escapes to begin a life of adventure. Jim is the slave who is accused of murdering Huck by the aunt. In their race for safety, Jim and Huck meet, build a raft and flee together down the Mississippi River. Their journey of adventure and friendship is permeated with humor, injustice, and cruelty. Ample quantities of Twain’s own riverboat experiences are richly interwoven. Samuel Clemens openly depicts the racism of this period, not with the sledgehammer commentary of Harriet Beecher Stowe in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” but with a poignant razor wit that both enlightens and cuts you to the heart while laughing at the outlandish antics of Huck and Jim. One of Huckleberry Finn’s characteristics which makes him a classic American personality is his deep caring for people, appearing to stop at nothing - even at times unscrupulous means - in order to help someone. In a world of con men and slavers, Huck and Jim have only each other to rely on, a trust that is brilliantly demonstrated, again and again. It is emotionally moving literature that does not condone racism but satirically attacks it with great subtlety.

John T. Lewis was born in Carroll County, Maryland, on January 10, 1835, a free black man. He joined the Pipe Creek Brethren congregation in the fall of 1853 after being baptized at the Meadow Branch church by Elder Philip Boyle. He later transferred his membership to the Beaver Dam and Marsh Creek congregations. In 1862, Lewis moved to upper New York state where he discovered that Brethren had not established congregations. Elmira became his new adopted home town, and he was deeply respected by the community. His repute among the citizens of this town would increase greatly after saving the lives of three people. Returning home from market with his wagon, he was startled to see a carriage pulled by a runaway horse, erratically lurching and careening about the road with three very frightened women aboard. Quickly, he pulled his wagon to the side of the road, just in time to leap from it onto the bridle of the spooked horse. Lewis was tall and strong. He managed to successfully bring the horse and carriage to a complete stop, at which point he became acquainted with the occupants: Mrs. Charles Langdon, her daughter Julia, and a nurse. General Charles Langdon, the grateful husband, and Mrs. Langdon were the parents of Olivia L. Langdon who married Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) in 1870. Clemens first learned of Olivia while traveling to Europe aboard the eighteen hundred ton steamer Quaker City, when he viewed her picture in an ivory miniature in the stateroom of her brother. It was love at first sight. During the trip, he befriended the other passengers, and their mutual adventures served as a basis for his writing of The Innocents Abroad, probably the nearest to history of Clemens’ travel books.

Gratitude was expressed to Lewis for having saved the lives of the three women, first in the amount of one thousand dollars from General Charles Langdon, fifty dollars and a personalized set of books from Samuel Clemens who was visiting the Langdons, and four hundred dollars from Mr. Crane, the man with whom the three women had been visiting that day before their galloping return. Lewis then started working for the Langdons as their personal coachman. He and Clemens became very good friends. Later, when Clemens was writing his famous novel Huckleberry Finn, it was the warm and friendly personality of John T. Lewis which served to inspire the personality of Jim, the runaway slave and friend of Huck. “I have not known an honester man nor a more respect-worthy one” - Samuel Langhorne Clemens.

The restored Pulpit Bible remained in the Little Dunker Church until the Mumma congregation later became inactive. In 1914, the Bible was secured in the vault of the Fahrney-Keedy Home near Mapleville, Maryland. Around 1937, the Bible was given into the custody of Mr. & Mrs. Newton Long, for she was the great-great-granddaughter of Daniel Miller who originally presented the Bible to the Mumma congregation in 1851. In the course of time, as all people eventually move into eternity and relinquish their possessions, it was decided to transfer the Bible for safe keeping to the Washington County Historical Society till such time as a permanent repository could be established.

Following the battle, Elder D.P. Sayer called for contributions to restore the Mumma Church. Extensive repairs were made and the Little Dunker Church was rededicated the next year (1863). The congregation decided to move to a new church location in Sharpsburg around 1916 and the battlefield church was abandoned. In 1921, an extremely violent storm collapsed the structure with the brick walls being nearly reduced to their foundations. What remained was later purchased by the U.S. Government (1951) which initiated a major effort to restore the church and its furnishings to their pre-Civil War appearance. This was finally completed in 1962 through a cooperative effort between the National Park Service, the Washington County Historical Society, the State of Maryland, and the Church of the Brethren. The Washington County Historical Society then presented the Bible to the National Park Service which has it on display in the Museum Section of the Antietam National Battlefield Visitor Center.

Photo Credits:

All modern photographs by Ronald J. Gordon © 1998, 2002. Other photographs, images, or reproductions are displayed with respect to intellectual property and compliance to all known Copyrights.

Bibliography:

A complete listing of all resource materials involved in the production of this resource can be found at the bottom of the home document. Included are hard print literature, numerous maps, graphic images, and links to related web sites. Unlisted are numerous trips to the battlefield, visits to associated congregations, and personal interviews.