Written by Ronald J. Gordon Published: August, 1998 ~ Last Updated: March, 2013 ©

This document may be reproduced for non-profit or educational purposes only, with the

provisions that this document remain intact and full acknowledgement be given to the author.

|

|

James Buchanan, President of the United States from 1857 to 1861, endeavored to govern a fast-growing nation that was slowly beginning to fragment over the question of slavery, especially its growing acceptance in the western territories. Political division over this evil was long evident in the eastern States, but the expansion of slavery into the West incited both sides to work more forcefully, because full acceptance in these new territories would give more clout towards determining the final outcome of popular opinion in the East, and subsequently the whole nation. These western States became a hotbed of Slave and Abolitionist activity, in an early concerted effort to sway opinions. Buchanan inherited this problem when his predecessor, Franklin Pierce (1853-1857) and the U.S. Congress repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820 with the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 (for the purpose of building a railroad from Chicago to California). The former Act which had banned slavery in the new Territories was replaced with the latter Act which permitted each to decide the issue for themselves. A modest flood of Northerners and Southerners entered Kansas with every intent of swaying opinions and votes in their respective directions, using lobbying, extortion, and murder. When violent hostilities erupted, the spree of killings was suppressed only with the deployment of Federal troops. Some historians contend that the Civil War really began in Kansas. Slavers and Abolitionists were tenacious on building their best case for victory, and hopes ran high for political control in the 1860 elections. Abraham Lincoln won the Presidential election mostly because of a splintering of the Democratic opposition into a four-way race. This not only left Lincoln’s party holding a narrow margin of political control, but instituted a new departure from the Jacksonian / Democratic control of the previous 32 years. Lincoln was previously known as a strong advocate of freedom, and proponents of slavery in many southern States became enraged. With such an opponent in the White House, their hopes of political control and preserving slavery evaporated before their faces. In just over a month from the November elections, South Carolina seceded from the Union (December 20, 1860) and was followed within two months by Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Texas, and Louisiana. The Confederate States of America (CSA) was formed on February 9, 1861.

President James Buchanan (Lincoln’s predecessor) was perceived as a lame-duck for much of his last year in office, because he was not exhibiting the leadership or vision that could have avoided much bloodshed, Constitutional impasses, partisan stalemates, and finally the alienation of his own party which helped to split the Democratic ticket in the 1860 elections. He was an intellectually capable person, but did not seem to grasp the reality of Northerners not accepting Constitutional arguments that would favor the South; nor did he understand how Sectionalism was realigning political parties. The Whigs were being destroyed which resulted in the creation of the Republican Party. It has been suggested that a more aggressive policy toward the West combined with greater statesmanship in the East could possibly have avoided the Civil War, or dramatically reduced the seriousness of an emanate conflict. Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney delivered the Court’s landmark opinion in the famous Dred Scott case on the second day of Buchanan’s term in office. Scott had been a slave to a Dr. John Emerson and traveled with him through non-slave States. When Emerson died, Scott sued for freedom because he had lived in free States. The Court ruled that non-citizens (slaves) did not have the privilege of being able to sue in a federal court. The timing was politically disastrous and this Decision would overshadow the new President for his full term. Following the election of Abraham Lincoln in November, 1860, Buchanan introduced an unofficial policy of inactivity, an earnest waiting to be able to leave the White House. Historians cite that his lack of interest in State matters from November, 1860, until March of 1861, actually permitted the seceded southern States to organize themselves more completely. Lincoln, unfortunately, inherited a fractured nation with no clear Administrative vision.

On March 2, 1861, two days before Lincoln was inaugurated on March 4, the US Congress passed the Morrill Tax Act which raised tariffs on imports. It was named after its sponsor, Justin Smith Morrill of Vermont who was also co-founder of the Republican Party. The first Act of March raised the percentage from 17% overall and 21% on dutiable items to 26% overall and 36% on dutiable items. Further increases much later raised those percentages to 38% and 48%. The Morrill Tax significantly hurt the Southern states because they exported cotton to Britain, which then exported goods to the South. This tax placed a huge burden on the Southern states because they represented about 30% of the population but paid nearly 80% of the tax. The Union was enriched and the Confederacy was impoverished. Predictably, many Southerners were forced into bankruptcy. Some have claimed that the Morrill Tax was the cause of the Civil War, but the Southern states had seceded from the North the previous year. Slavery was the principal reason for the secession. Passage of the Morrill Tax only further embittered Southerners towards the North.

Representatives from the various Confederate states meeting in a series of Conventions then found themselves in a heated struggle to select a national leader. Many candidates were considered but none offered sterling qualifications. Civil War historian William C. Davis, Jefferson Davis: The Man and His Hour, chronicles the selection process. Alexander Stephens, one of the most brilliant minds of the Confederacy was one of the first candidates, but his negative qualities of being short in stature, mixed with a drug habit soon diminished his opportunity. Further, he opposed secession from the Union at first. Georgia bred U.S. Senator Robert A. Toombs, a turbulent secessionist, was another possibility but his misdemeanors with alcohol frightened some delegates. They may have conjectured among themselves: “Should we chance having an inebriated President receiving foreign dignitaries?” A reluctant consensus finally engaged West Point graduate Jefferson Davis as their President with Alexander Stephens as Vice-President. Toombs was embittered and pursued military service where he later commanded troops at the battle of Antietam as a Brigadier General, repulsing the attempts of General Ambrose Burnsides to cross a bridge during the Third Phase of this battle. The Georgia General placed hundreds of Georgian sharpshooters on the bluff overlooking the (Burnside) Bridge, and virtually had a turkey shoot as Union soldiers had to come out into full view in order to get across the open structured bridge. Stephens soon discovered that his Vice-Presidency would exist in the deep shadow of Jefferson Davis who rarely delegated responsibility. It was a tremendous disappointment.

Having dissolved their connection from the Union, the Confederacy now faced questions of legal ownership concerning Union property and military installations on their homelands. Such a circumstance involved South Carolina, for the Union garrison at Fort Sumter was prominently located on a small island in the middle of the entrance to Charleston harbor. This fort had not been resupplied since the previous December and Lincoln ordered that reinforcements be sent immediately. Realizing a serendipitous window of opportunity over their weakened condition, General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, commander of the provisional forces of Charleston, requested its immediate surrender. Union Commander Major Robert Anderson naturally refused. On April 12, at 4:30 a.m., a steady bombardment commenced that would force the Union garrison to surrender after two days of relentless shelling. President Lincoln then responded by issuing orders on April 19, for a naval blockade to surround all southern ports. The Civil War had begun (unless Kansas is considered).

Robert E. Lee (1807-1870) son of a Revolutionary War hero, enjoying over 25 years of service in the United States Army and a former Superintendent of West Point was widely known for his impeccable character and keen sense of honor. When offered supreme command of the Union Army, he gracefully declined because of unwavering loyalty to his homeland of Virginia: “I cannot raise my hand against my birthplace, my home, my children” and respectfully departed for Richmond. His homeland of Virginia seceded on April 17th and was then followed by Tennessee, North Carolina, and Arkansas. Lee accepted command of the Army of Northern Virginia and began developing a strategy to achieve victory and legitimacy, a novel undertaking when considering that the two capitals of Washington and Richmond were less than one hundred miles apart. Lee also developed a courteous approach to psychologically manipulate Jefferson Davis who often seemed aloof or mentally distant from the urgency of the moment.

|

George B. McClellan Union General |

|

Robert E. Lee Confederate General |

Unlike Federal commanders who did not similarly “work” President Lincoln to their advantage, Lee received everything that he asked from Davis for at least these reasons: he wrote letters often to Davis from battlefields, giving him information that varied from substantive to trivial. In these letters, Lee frequently and wisely made statements similar to: “this is what I want to do and this is how I propose to accomplish it; however, I bow to your superior judgement in these matters.” Additionally, Lee continued to give Davis a string of military victories, be they convincing or marginal. If Lee asked for troops, Davis supplied them. If Lee asked for guns and ammunition, Davis somehow found them. Not all Confederate generals, in like manner, so courted the attention of Jefferson Davis. General Joseph E. Johnston rarely corresponded with Davis from the battlefield, and he was continuously aggravated at being ignored by the Richmond administration. Union military leadership was initially weak because many Southern bred Union officers resigned their commissions for much the same reasons as Lee. Federal troops were small in number and likewise did not have an immediate strategy for victory. Lincoln had won the Presidential election mostly because of a splintering of the opposition into a four-way race which left his party with not only a narrow margin of political control, but instituted a new departure from the Jacksonian / Democratic control of the previous 32 years. Now the lines were succinctly drawn between an 11 State Confederacy with a population close to 9 million of which about 4 million were slaves, and the Union of 21 States with a population of nearly 20 million, few slaves, but all the resources necessary to fight a protracted war. Lee was well aware of the necessity of an early victory, for the South did not possess nearly as many resources as the North, and Lincoln’s naval blockade was successfully restricting their importation of goods. Civil War historian Joseph Harsh, Confederate Tide Rising, writes: “Southern resources could not support an overly long war. Once the contest has started, a logistical hour glass had been set on end and its sands ran relentlessly against the Confederacy.” Was victory ever possible for the Confederacy under these conditions? Most Civil War historians generally agree that victory could have been realized, but only if early and without a significant loss of troops or munitions. Lee could not afford a long war nor a high number of casualties. After the first year, Lee developed a new strategy, a bold new vision to launch far beyond the initial stymied contests of Union and Confederate armies chasing each other around the hills of Virginia. Lee then devised a completely new approach that might swing the pendulum of Northern opinion in his direction. This vision would eventually bring him to a Little Dunker Church along the Antietam Creek in the new horizon of Maryland.

Military command of Union forces was a slow revolving door through which passed several qualified generals who, sooner or later, did not fully meet the expectations of President Lincoln: Winfield Scott and Irvin McDowell were replaced by George McClellan, who was replaced by John Pope, who was replaced by George McClellan, who was replaced by Ambrose Burnsides, who was replaced by Joseph Hooker, who was replaced by George Meade who served to the wars end under Ulysses Grant. Supreme command of southern forces was held by Robert E. Lee from the time of his commissioning until he left Appomattox Court House, stately riding upon his white horse Traveller.

Philadelphia native George Brinton McClellan (1826-1885) graduated from West Point in 1846 with a degree in engineering. He studied military campaigns in Europe and developed the “McClellan Saddle” which was also used by the Prussian and Hungarian cavalry. Leaving the military in 1857, he began working for the Illinois Central railroad as chief engineer and later its vice president. When the Civil War broke out, he reentered military life and quickly rose through one level of command after another because of his remarkable organizational skills. His dictatorial personality gained him the title of “The Young Napoleon” and his frequent hesitations in moving troops on the battlefield would finally cost him supreme command of the Army of the Potomac following the Battle of Antietam. His military career would end in front of, a Little Dunker Church.

After more than a year of nearly stalemated warfare and mostly occurring in his homeland State of Virginia, General Robert E. Lee decided to take the war north of the Potomac River with the hope that several factors may cause northern States to pressure Lincoln to settle on more agreeable terms. After soundly whipping the Union army at 2nd Bull Run or Manassas (August, 1862), Lee’s army of Northern Virginia was riding on an air of enthusiasm. His Generals were jubilant, almost effervescent. On these circumstances, Lee believed that it was the opportune moment to implement his vision of taking the war into the north. He crossed the Potomac River into Maryland for, at least, these reasons:

- Maryland was an undecided border state that may swing to the Confederacy

- Take the suffering of war into the northern States to force a decision

- Relieve Virginia of Union troop occupation so farmers may safely harvest

- Virginia harvest would then feed Lee’s army through the coming winter

- Maryland offered rich supplies for his hungry and poorly clothed troops

- Influence upcoming Congressional (Union) Elections for a possible settlement

- Diplomatic recognition from European capitals would provide legitimacy

- The chance that England and France might join the war or at least aid the South

- Northern States might begin to question Lincoln’s leadership

During the morning of September 4, 1862, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia crossed the Potomac River and soon arrived in the town of Frederick, Maryland. He directed his officers to “buy” provisions instead of the usual pillaging associated with occupying armies, so as to demonstrate his benevolent or politically calculated intentions. Lee then issues A Proclamation to the People of Maryland to hopefully charm their sympathetic ears. He devised a plan that would entrench his army at Hagerstown, with the ultimate goal of following the rail line to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, a key rail center of the Union. Now the stage was slowly being set for a major confrontation with the Union army. This epochal event would transpire near the Antietam Creek, in the vicinity of Sharpsburg, Maryland, right in front of a Little Dunker Church.

Confederate artillery units (left) fire on Union General John Sedgwick’s brigades coming out of the East Woods (right), to prevent them from capturing the high ground at the West Woods next to the Dunker Church. This large mural was painted by Captain James Hope who was injured in a previous battle and consigned to the sidelines as a map maker. |

Lee’s otherwise brilliant plan is frustrated by several factors: McClellan has restored the Army of the Potomac from its humiliating defeat at 2nd Bull Run or Manassas in a matter of days instead of weeks, the Union garrison at Harpers Ferry did not flee as expected but withstood a prolonged attack before surrendering, and Lee’s entire Maryland plan is fatefully discovered in one of their deserted encampments near Frederick by a Union soldier, the famous Order 191 that was wrapped around three cigars. Antietam National Park guides confidently explain that it was the “cigars” themselves that surely caught the eye of that Union Private and not just the bundle of paper, because a cigar would have been a supreme luxury during wartime. As McClellan hastily moves due west, Lee is dismayed to find himself in an extremely weakened position, because nearly half of his troops are to the south with General Stonewall Jackson at Harpers Ferry and the rest are divided between himself and General James Longstreet who is on a northerly march toward Hagerstown. Lee quickly fortifies all three passes over South Mountain to block the progress of McClellan and urgently calls for all troops to regroup on a wide ridge extending north from a little town called Sharpsburg. It was a gratuitous opportunity to encamp on this high ground, a strategic position from which to observe all movements coming over and down the western slope of South Mountain.

However, Union troops were successful in breaching the Confederate blockade at the mountain passes, and easily crossed Antietam Creek by Tuesday afternoon. That evening it was apparent that heavy fighting would ensue with the usual artillery barrages at dawn. The Army of Northern Virginia owned the high ground and the Union could dislodge them only after a formidable process of extricating their troops from well prepared fortifications. Both sides were prepared for a full scale battle, not knowing that this would be not only the bloodiest strife of the entire Civil War but also in the history of United States warfare, all without a sterling victory for either side. Death would gormandize its richest number of wartime casualties for a single day of fighting. Wednesday, September 17, 1862, would become a monumental witness to future generations of the horridness and inconclusiveness of war. Three separate attempts or phases by Union troops failed to permanently dislodge the entrenched Confederate forces. In two areas, the same ground was lost and won several times. By evening it was a tactical stalemate. Lee was unable to progress further north, the Potomac River was to his rear, and McClellan could not advance up the ridge. Historians usually bestow Lee with the humiliation of defeat because his dream of northern progress was vanquished, but victory is not easily awarded to McClellan because he was unable to dislodge his rival with almost twice the number of troops and he then permitted Lee to retreat without pursuit. After a string of such battlefield hesitancies to capitalize on obvious good fortunes, McClellan was fired by President Lincoln.

Troops moving, cannons shouting, bullets hurling, men screaming, and officers commanding were the expected norm. Events occurring on this damp foggy Wednesday are best explained by associating them with each of Three Battle Phases: Morning, Mid-Day, and Afternoon. McClellan’s hopes of dislodging Lee from the top of this elongated ridge were concentrated in strategies that seemed to be underestimated from the beginning. The Army of the Potomac would discover this to be a feat well beyond anything they had anticipated. Loss of human life would also be greater than anyone could ever have imagined.

Morning |

From the North Woods, Union General Joseph Hooker’s dawn artillery pounds the Confederate troops of Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson standing in the Miller Cornfield and beneath the giant oak trees or limestone outcroppings of the West Woods surrounding the Little Dunker Church. Union officers looking across these fields at first believed the Church to be a School House. Hooker drives Jackson back almost to the Church but is then forced to retreat after Jackson is reinforced. This first effort was an attempt to get around Lee’s left flank and also cut off his retreat across the Potomac River. Union General Joseph Mansfield then tries to march through the flattened corn field but is also repulsed. Union General John Sedgwick’s division then succeeds in advancing into the Dunker West Woods but McLaws and Walker’s troops kill or wound more than half of his division - over 2,200 men die from close range fire in about fifteen minutes. These bloody exchanges inhured over twelve thousand men from both armies in almost 3½ hours, which means that men were suffering at the rate of about one per second (3½hr x 60sec x 60sec = 12,600). See Henry K. Douglas’ eye witness account of this phase below. |

Mid-Day |

Union Generals William French and Israel Richardson moved their divisions up this elongated ridge to assist Sedgwick but veered slightly to their left and directly into the center of the Confederate line under General Daniel Hill who was reinforced by General Richard Anderson. An 800 yard long Sunken Road, worn deep over the years by heavy grain wagons made an ideal defense for Hill’s troops to aim at Union forces marching toward them in almost parade rank formation. The roar of gunfire was loud and long. Anderson’s backup division of 3,400 troops was mostly destroyed. One Union officer later wrote: “For three hours and thirty minutes, the battle raged incessantly without either party giving way.” Over 5,500 men died in the area of Bloody Lane. See General Gordon’s eye witness account of this phase below. |

Afternoon |

Union General Ambrose Burnside had been trying for hours to move a corps of 12,000 men across this 125 foot narrow stone arch bridge over Antietam Creek to the southeast of Sharpsburg, in an attempt to over-run Lee’s right flank. On the west side of the bridge and greatly outnumbered was General Robert Toombs with about 400 Georgia sharpshooters who easily repulsed Federal troops by aiming down on them from a wooded bluff. Level fields to the east side of the bridge made Union troops easy targets; a virtually turkey shoot as the men in Blue had to come out into full view in order to get across the open structured bridge. Only with the promise of whiskey did Union troops propel themselves into a suicidal charge across the bridge. Fortune rings unpredictably though, for as the Confederates were finally being dislodged from this hill and driven toward Sharpsburg, they were reinforced by the arrival of General Ambrose Hill who had just led his troops on a hurried seventeen mile return march from Harpers Ferry. Georgia born Robert Toombs, who narrowly missed being selected as Vice-President of the Confederacy, was elated to welcome Hill’s tired but committed troops. This unnamed bridge was later called Burnside Bridge. See David L. Thompson’s eye witness account of this phase below. |

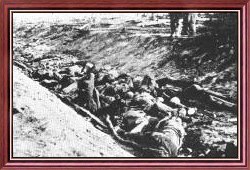

Following nearly twelve hours of heated battle, troop positions had not varied much from when they started but around 23,000 men and boys had been killed, wounded or missing in this most ghastly of wartime engagements. Almost two thousand men slain per hour. Bodies were thickly sprawled in diverse mangled forms in the Miller Cornfield, such that one could almost walk across it without stepping on bare ground. Union General Joseph Hooker writes: “In the time I am writing, every stalk of corn in the greater part of the field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife.” To his left and farther south, was a Sunken Road (later to be called the Bloody Lane) which had been deepened over the years by the weight of heavy grain wagons. Confederate forces lay prone in this depression, to repulse any attempt at penetrating the Confederate center. It would soon be filled with dead bodies for much of its 800 yard length. Divisions battled against divisions in this area, killing thousands upon thousands of men in just beyond point blank range. General John B. Gordon (see below) relates how he directed his Confederate troops to wait in their prone positions until the Union soldiers had almost reached the lane. At his command, a simultaneous burst of galling rifle fire dropped rank after rank after rank, over and over and over.

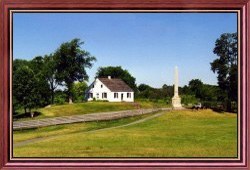

|

AUGUST, 1998 |

|

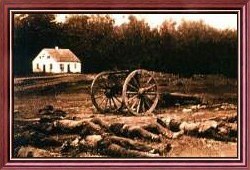

SEPTEMBER, 1862 |

Each time, the men in Blue would then retreat some distance only to form another series of ranks and march toward the men in Gray again. It must have been maddening for the rear most ranks to see their forward comrades dropping before the flame of so many riles, again and again and again. It must also have dumbfounded them to be marching with bulletless chambered rifles, in order to break through the enemy line with mounted bayonets only. Yes, that’s correct. Some of the Union soldiers were ordered to unload their guns and march with bayonets fixed, in the hope of penetrating the well entrenched Confederate line, and many of the Confederates were informed ahead of time that the rifles of this bayonet Corps were unloaded. They knew that they would be firing into helpless men at almost point blank range. The enormity of the slain was overwhelming and their concentration so deep that it was later coined Bloody Lane. Where grain had once spilled from overloaded wagons, a darkened covering of blood now stained the ground. The Little Dunker Church had witnessed more death before its doors than anyone could ever have imagined. The place where peace and non-violence had been preached now recorded the destruction of more souls dying in battle than any other day of battle in American warfare. The unnamed bridge across Antietam Creek may as well have been labeled Bloody Bridge, for thick was the blood from the men who died to cross its 125 foot span for the promise of whiskey. Thousands of men and boys would never return home, but their unburied remains would be viewed by thousands of people across the nation.

Photography had previouly visited and recorded the scenes of other battlefields, but this would be the first time that images of dead bodies would appear in photographic galleries and newspapers. So great was the number of dead soldiers and the length of time required to bury them that battlefield photographers, Alexander Gardner and James Gibson, had ample time to record their gory positions. It is through the eyes of these two men that we view the repulsive captivation of dead bodies lying in Open Fields, in Bloody Lane, and before the Little Dunker Church. These Matthew Brady hired craftsmen had nearly four days to move their photography wagon around the battlefield and record everything from rock ledges in the West Woods to everyday life in the village of Sharpsburg. Even though they had several days to record these images, many bodies were naturally being gathered and buried all the while, thus even their own photographs do not exhibit the battle’s full impact. In the Bloody Lane, one can see that most bodies had already been cleared from the left or southeastern portion. Immediately after the shooting had ended in the evening of September 17, this and many other scenes would most probably have been much worse. Although repulsive and disgusting to some, the faces of these dead soldiers evokes a strange captivation that may be a convincing tool for educating and hopefully ensuring that future generations will not tolerate such episodes of carnage again. These images add a human detail to the volumes of documentation, official reports, and unconfirmed experiences that remain to continually tell the story of this battle.

HENRY K. DOUGLAS: (Confederate: Staff member with General Stonewall Jackson)

"On my way to (General) Early, I went off the (Hagerstown) Pike and was compelled to go through a field in the rear of Dunker Church, over which, to and fro, the pendulum of battle had swung several times that day. It was a dreadful scene, a veritable field of blood. The dead and dying lay as thick over it as harvest sheaves. The pitiable cries for water and appeals for help were much more horrible to listen to than the deadliest sounds of battle. Silent were the dead, and motionless. But here and there were raised stiffened arms; heads made a last effort to lift themselves from the ground; prayers were mingles with oaths, the oaths of delirium; men were wriggling over the earth; and midnight hid all distinction between the blue and the gray. My horse trembled under me in terror, looking down at the ground, sniffing the scent of blood, stepping falteringly as a horse will over or by the side of human flesh; afraid to stand still, hesitating to go on, his animal instinct shuddering at this cruel human mystery. Once his foot slid into a little shallow filled with blood and spurted a little stream on his legs and my boots. I had a surfeit of blood that day and I couldn’t stand this. I dismounted and giving the reins to my courier, I started on foot into the wood of Dunker Church."

GENERAL JOHN B. GORDON (Confederate: Assigned by Lee to defend the Sunken Road)

"The brave Union commander, superbly mounted, placed himself in front, while his band in rear cheered them with martial music. It was a thrilling spectacle. The entire force, I concluded, was composed of fresh troops from Washington or some camp of instruction. So far as I could see, every soldier wore white gaiters around his ankles. The banners above them had apparently never been discolored by the smoke and dust of battle. Their gleaming bayonets flashed like burnished silver in the sunlight. With the precision of step and perfect alignment of a holiday parade, this magnificent array moved to the charge, every step keeping time to the tap of the deep-sounding drum. As we stood looking upon that brilliant pageant, I thought, if I did not say, What a pity to spoil with bullets such a scene of martial beauty! But there was nothing else to do. Mars is not an aesthetic god."

DAVID L. THOMPSON (Union: Company G, 9th New York Volunteers with General Burnside)

"Human nature was on the rack, and there burst forth from it the most vehement, terrible swearing I have ever heard. Certainly the joy of conflict was not ours that day. The suspense was only for a moment, however, for the order to charge came just after. Whether the regiment was thrown into disorder or not, I never knew. I only remember that as we rose and started, all the fire that had been held back so long was loosed. In a second the air was full of the hiss of bullets and the hurtle of grape-shot. The mental strain was so great that I saw at that moment the singular effect mentioned, I think, in the life of Goethe on a similar occasion - the whole landscape for an instant turned slightly red."

MAJOR-GENERAL J.E.B. STUART (Confederate: Crossing the Potomac River after the battle)

“At the edge of the river, and in the water, stood an ambulance filled with wounded men. The cowardly driver had unhitched his horses, crossed the river, and had left his suffering comrades to the mercy of the foe. The poor fellows begged piteously to be carried to the other side. General Gregg lifted his hat, and said to his soldiers: ‘My men, it is a shame to leave these poor fellows here in the water! Can’t you take them over the river? In an instant, a dozen or more strong men laid hold on the ambulance and pulled it through the water, in most places waist deep, amid the shouts of the rest, who sang - Carry me back to Old Virginia.’”

NEW YORK TIMES, October 20, 1862 (Northern Newspaper: Commenting on photographs of Antietam)

"The living that throng Broadway care little perhaps for the Dead at Antietam, but we fancy they would jostle less carelessly down the great thoroughfare, saunter less at their ease, were a few dripping bodies, fresh from the field, laid along the pavement. There would be a gathering up of skirts and a careful picking of way ... Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along streets, he has done something very like it ... We should scarce choose to be in the gallery, when one of the women bending over them should recognize a husband, a son, or a brother in the still, lifeless lines of bodies, that lie ready for the gaping trenches ... Homes have been made desolate, and the light of life in thousands of hearts has been quenched forever. All of this desolation, imagination must paint for broken hearts cannot be photographed."

President Abraham Lincoln visited the battlefield on October 3. Although he was not an eyewitness “of” the battle, he was the most important witness “to” the battlefield. He was greatly disturbed by yet another occasion of General McClellan’s hesitations to capitalize on obvious windows of opportunity. Remembering with disappoint the many times that the General might have pursued the Confederate army or taken Richmond and did neither. In January, 1862, McClellan had been ordered to appear before Congress to explain his handling of the war situation. Senators Benjamin Wade and Zachariah Chandler gave him a brutal examination. Wade asked the General why he would not directly attack the Confederate Army. McClellan stated that it takes time to prepare necessary routes in case of retreat. Chandler then harshly condemned the General for being more concerned about retreating than advancing. The two Senators almost pictured McClellan as being more afraid of the Confederacy in Richmond than the Union in Washington. It was Alexander Gardner who took the now famous photograph of Lincoln and the soon-to-be-fired McClellan inside the General’s tent, which some have humorously titled: “Friend or Foe.”

Lincoln was quickly growing weary of McClellan’s repeated hesitations, miscalculations, and general overcautious handling of the war. He was extremely disappointed that Lee was able to escape from Antietam, without even a chase. In one last effort to goad the General toward a decisive confrontation, Lincoln wrote the Frustration Letter which expressed the Presidents frustrations that the enemy was more capable at taking greater risks and winning under greater disadvantage. “All the distinguished in the land ... would almost worship you if you would put a fighting general in the place of McClellan” writes Mary Todd Lincoln to her husband on November 2, 1862. With no military or political solution visible, Lincoln decided that he could tolerate the situation no longer. On November 7, President Lincoln recalled the General to Washington with another letter that, in part, contained these words: “My dear McClellan: If you don’t want to use the Army, I should like to borrow it for a while.”

Casualties in the Battle of Antietam are much less than the three day campaign at Gettysburg which impacted an estimated fifty-one thousand lives but this battle near Sharpsburg, Maryland, holds the record for the greatest number killed, wounded or missing from “one day” of fighting. Exact totals for each phase are difficult to calculate because historical records contradict each other. As is true in most battles, a number of the wounded died sometime later. A few sources include these later dead in their original battle count and some do not.

| PHASE | UNION | CONFEDERATE | SUBTOTALS | TOTALS | OTHER CONFLICTS | ||

Morning |

|

||||||

| Cornfield | 4,350 | 4,200 | 8,550 | ||||

| West Woods (Dunker Church) |

2,200 | 1,850 | 4,050 | 12,600 |

|||

| Mid-Day | |||||||

| Sunken Road | 2,900 | 2,600 | 5,550 | 5,550 |

|||

| Afternoon | |||||||

| Burnside Bridge | 500 | 120 | 620 | ||||

| Final Attack | 1,850 | 1,000 |

2,850 | 3,470 | |||

| Missing/Captured | 750 _______ |

1,020 _______ |

1,070 | 1,070 _______ |

|||

| Totals | 12,550 | 10,790 |

22,690 |

|

Resources:

22,720 - History.net 22,720 - National Park Service 22,719 - PBS.org 22,717 - Civil War Trust 22,700 - Antietam on the Web US Department of Defense US Department of Veterans Affairs. See also Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Civil War: 4,710 dead, 18,440 wounded, 3,043 missing for a total of 26,193. |

The pictures of the dead at Antietam stunned the nation. Matthew Brady’s New York photo gallery offered people their first opportunity to view dead bodies on a battlefield. Visitors were overwhelmed at the carnage and the extent of destruction to human life. How could a single day of fighting result in so many casualties? The following suggestions hope to explain why Antietam was such a pivotal moment in the timeline of military technology and methodology. A time when battle tactics and new weaponry would decide how all future wars would be fought.

Historians have called the Civil War the last of the ancient wars and the first of the modern wars. These years saw more military innovations than centuries of previous warfare. New introductions were rifling which extended the range of both musket and cannon, repeating rifles and carbines, artillery changing from bronze and iron to steel, ironcald battleships, and the first organized use of ambulances. In all previous wars, the weapons were generally the same and victory was decided by the more brilliant thinkers. During the Civil War, innovation and experimentation was constantly altering old methodologies. Far too many generals were slow to understand the significance of the new innovations and take advantage of them.

Napoleonic Battle Formations

Officers on both sides were a product of military schooling that still continued the use of Napoleonic tactics which focused on visible cues given by field commanders in synchronization with predetermined marching formations. In Old World style of battle, infantrymen were spaced out in large blocks over a wide area and took visual promptings from distant commanders because they were unable to hear clear instructions. Modern battle tactics are just the opposite. Fighting units are very close to their commanding officer and take verbal cues, or hand signals if the enemy is within hearing distance. Old World tactics included predetermined formations and robotic movements that required lots of practice and good memory. Frequently the smoke of battle obscured visual cues so a block of troops would continue to march and engage the enemy through those same formations. Bayonet charges were often successful in breaching an enemy line because of the short range of the smooth-bore musket. The basic premise of troop formations is not too much unlike a high school marching band that rigidly steps through various parade movements on a football field during half-time, except that they are using musical instruments which do not shoot at fans and spectators. One offensive solution of the short range musket was to group men close together and fire in a collective shotgun pattern, assured that some of the bullets would certainly reach their mark. The officers on both sides were the product of these Old World tactics which had been employed as late as the Mexican War.

Innovation of the Rifled Musket and Cannon

Short range muskets such as the Brown Bess were employed during the Revolutionary War. It had a long barrel at 62 inches with a smooth bore of .75 caliper, and unfortunately was manufactured on foreign soil. President George Washington personally selected the little town of Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1794 to be the home of the American Armory whose principal business would be to manufacture firearms. During the Revolutionary War it has been an arsenal for storing muskets, cannon, and the manufacturing of ammunition. Following the war the government continued to maintain the facility as a place to store guns for future conflicts. Production of smooth bore flintlock muskets began in 1795. A second United States Armory and Arsenal was established in the town of Harpers Ferry, West Virginia in 1799, which explains why its capture was so important to General Robert E. Lee during the Maryland Campaign, and the purposeful target of the John Brown Raid of 1859. The last smooth bore musket began at Springfield in 1842 but was also the first to have fully interchangeable parts. Rifling of the barrel was introduced in 1855 which spun the projectile like a football. This created a longer trajectory because of less wind resistance and greatly improved accuracy.

However, the smooth bore musket remained the infantry weapon of choice because a bullet large enough to touch the rifling was also hard to ram down the barrel, whereas the smooth bore musket had a caliper bore that was larger than the actual projectile, so it quickly slipped down the barrel. After several firings of these early rifles, black powder residue would build up in the grooves and require cleaning. This produced a dilemma: a more accurate weapon with a longer range was less desirable than a shorter range weapon that was less accurate. In 1849, Claude-Etienne Minie a captain in the French army developed a cylindrical projectile which was slightly smaller than the rifled grooves but would expand against them when fired. This enabled it to both spin and also clean the barrel at the same time. This development completely revolutionized military tactics on the battlefield because troop formations could be successfully targeted while marching in areas that were previously considered to be safe and beyond range. Old World style bayonet charges would be futile. Springfield began issuing rifles in 1855 but the model of choice during the Civil War was the 1861. Unfortunately they were not produced in great enough numbers, so the smooth bore was still the primary weapon during the first two years.

| 1842 SMOOTHBORE Musket | 1861 RIFLE Musket | |

| .69 | Caliber Bore |

.58 |

Musket Ball  |

Projectile |

Mini-Ball Mini-Ball |

200-250 yards |

Maximum Range |

450-500 yards |

| 70-90 yards | Accuracy Range |

250-300 yards |

Human reasoning is hard to change. What has been learned and practiced is deeply imbedded. Change or adjustment becomes difficult. The rifle had proved to be far superior to the smooth bore yet the armies of Antietam marched in the same Old World style Napoleonic formations. This would be the battle where hard lessons would be learned. It was not the first Civil War battle to witness the use of rifles, but it was the first battle to see them used in a large enough scale that would make a notable difference. For the first time in history, rifles made the defense superior to the offense. Numerous formations of men in colorful battle uniforms smartly strutting to the beat of parade drums would be cut down like a turkey shoot. These men had been taught and drilled hour after hour to march in linear blocs, shoulder to shoulder, and never to break ranks. Wave after wave of marching men would die in full view of commanding officers who did not relent under such obvious circumstances but continued to order additional waves of marching men to their immediate doom. Old World style bayonet charges would yield horrific casualties. Futility would enjoy one of its finest hours.

Artillery witnessed the same transformation of smooth bore to rifling. The smooth bore 1857 Model Napoleon firing a 12 lb. projectile up to 1,600 yards was the most favorite cannon of the war. The Union had 108 at Antietam and the Confederates 72. It was slowly being replaced with the newly developed Parrott which fired a 10 lb. projectile up to 1,800 yards. Its tube was much stronger and lighter which made the entire piece more maneuverable. Robert P. Parrott graduated from West Point in 1824 and was later assigned as an inspector of ordnance at the West Point Foundry at Cold Spring, New York, a privately administered firm. He resigned from the military to become its superintendent. Parrott experimented with producing stronger cannon tubes and rifling with corresponding projectiles and received a patent in 1861. Rifled cannons were used very effectively at Antietam because each battery could place themselves out of smooth bore range and still reek havoc on enemy positions. The deployment of both types of cannon produced an nightmarish scene with a cacophonous roar that Confederate Colonel Stephen D. Lee referred to as “artillery hell.” (See detailed comparison at Field Artillery in the American Civil War

Poor Union Cavalry

During the Civil War, the main purpose of the cavalry was reconnaissance, gathering intelligence, and harassment of the enemy. These troops were mounted on horseback and could quickly move around the battlefield. Information gathered during their gallant exploits was invaluable to a field commander. Guesswork was replaced with stratagem. Assumptions turned into facts. Without the use of cavalry, an army was not able to see the full placement of the enemy. Positioning and commanding of troops resulted in little more than fool-hardy leaps of faith. Confederate General James E.B. Stuart had previously distinguished himself as a brilliant cavalry officer. In the Peninsular campaign in which General McClellan attempted to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond, he was entirely embarrassed by Stuart’s audacious escapades. General Lee ordered Stuart to reconnoiter the right flank of the Army of the Potomac and upon discovering it to be completely exposed, Stuart exceeded his orders by making a full circuit around McClellan’s army. This resulted in a total humiliation of the Union Army which invigorated Southern morale. When Stuart was killed during the Wilderness Campaign (1864), General Lee lamented that he had lost “his own eyes.”

The Union Calvary at Antietam could best be described as: “What cavalry?” General McClellan did not trust a volunteer cavalry and never used it to any great effectiveness. Instead these men were assigned to be messengers and orderlies. Union Cavalry General Alfred Pleasonton was inept as a military officer and his field reports unreliable. Because of his charm for the ladies and stocking of champagne and oysters in his headquarters he was later dubbed “Knight of Romance.” From his headquarters in the valley next to Antietam Creek, McClellan directed his army without precise knowledge of Confederate placements at the top of the hill. Without knowing Confederate positions and strengths, thousands of Union infantry obediently followed blind commands into disaster.

"The cavalry at Antietam was employed well by the Confederates and poorly by the Federals. J.E.B. Stuart’s troopers screened the Army of Northern Virginia and kept McClellan from gaining accurate information about Confederate numbers and deployment. The Confederate cavalry tied in the armys flanks to the Potomac River. Being grouped in mass and practiced at maneuvering in large formations, they were able to develop combat power quickly."

"On the other hand, a large fraction of the Federal cavalry was frittered away in penny packets as guards and messengers at division and corps headquarters. Had the U.S. cavalry been properly deployed on the flanks, they could have detected A. P. Hill’s arrival and broken up or delayed his attack. Thus, Sharpsburg could have been carried and Lee decisively beaten with his route of retreat cut off. The failure of the Union cavalry at Antietam is not due to any lack of gallantry or good equipment, but rather to poor central direction by a defensive-minded commanding general."

National Park Ranger/Historian Paul Chiles

One example of blind engagement by Union troops was the utter chaos that developed in the West Woods just north of the Little Dunker Church on the Confederate left flank. It was the scene of some of the greatest confusion of the entire battle. A little after 9 a.m., General John Sedgwick’s division led by General Edwin Sumner crossed the Hagerstown Pike and into the West Woods. Considering the fact that there had already been three full hours of killing in the nearby Miller Cornfield, it would be entirely appropriate for a field commander to want to know exactly what circumstances lay before him in this wooded area. Good cavalry reconnaissance would have provided such information, which would have been: General Stonewall Jackson along with Generals Early, Walker, Hood, plus the newly arrived reinforcements of General McLaws. In other words, over 10,000 troops were hidden in a large semicircle quietly waiting for Union troops to enter the trap.

"Unmolested, they crossed the pike and passed into the West Woods. Almost surrounding them were Jackson’s quietly waiting 10,000. Suddenly the trap was sprung. Caught within a pocket of almost encircling fire, in such compact formation that return fire was impossible, Sedgwick’s men were reduced to utter helplessness. Completely at the mercy of the Confederates on the front, flank, and rear, the Federal lines were shattered by converging volleys. So appalling was the slaughter, nearly half of Sedgwick’s 5,000 men, were struck down in less than 20 minutes."

Antietam Historical Handbook Series, National Park Service, 1961

Union commanders had no “eyes” with which to understand Confederate troop emplacements. They had no cavalry to harass and disrupt Confederate movements. The entire day was a series of blind leaps of faith that resulted in confusion, stalemate, and embarrassment.

Tactical Errors

Every war has them. Some errors in judgement are small and some great. Some could have been avoided and some not. World War I was full of many incredibly stupid errors. They were so keenly described in “The Guns of August” by Barbara Tuchman that President John F. Kennedy made her book required reading for every member of his Cabinet.

Initial Hesitation

Football fans are well acquainted with the phrase: “He who hesitates is lost!” It also applies to the field of battle where generals lose due to hesitation or indecisiveness. Hesitation allows the opponent time to react and execute. Whether it be seconds, minutes, or hours, indecision robs you of the ability to command a situation.

Having twice the troop strength of Lee plus discovery of Order No. 191, Antietam has been called, “The battle that Lee could not win, and McClellan could not lose.” But he did in a purely tactical sense. McClellan is given victory by historians because Lee was prevented from advancing farther north. McClellan lost because he was fired by President Lincoln for hesitation. The paper wrapped around three cigars revealed that the Confederate army was divided into three weaker units, a cardinal sin in the business of war. This provided a golden opportunity for McClellan to drive a wedge between General Jackson at Harper’s Ferry and General Lee near Hagerstown. But he didn’t. Instead he hesitated which permitted Confederate forces enough time to regroup near Sharpsburg.

Did McClellan hesitate because of a trap? Was 191 a ruse? No. McClellan believed it to be genuine because he wrote that same evening of September 13 to General Halleck: “An order from General R. E. Lee, addressed to General D. H. Hill, which has accidentally come into my hands this evening, -- the authenticity of which is unquestionable...” This hesitation was not due to any contemplation of Confederate trickery?

Did McClellan hesitate because he was unsure of the Confederate troop strength? That’s what the cavalry is for! But McClellan didn’t even tell General Plesanton about the propitious discovery of 191. That was a capital blunder.

Did McClellan hesitate because he wanted to engage Lee at a better location? What better location could you ask for than to have the enemy with their backs against the Potomac River?

Poor Coordination

McClellan’s original battle strategy called for a simultaneous attack on both Confederate flanks. When one side fell, his middle would charge directly at the Confederate center while the successful flank would drive around behind and hit the Confederate back center, and thus surround that entire side. It never happened. General Hooker properly attacked the Confederate left on cue at 6 a.m. but General Burnsides did not start until about 1 p.m. This flawed the entire plan. The actual reason for this delay is still not clear.

Flawed Strategyn

Union General Burnside’s repeated attempts to cross the Lower Bridge (later named after him) was foolhardy since this small creek could have been crossed on any one of Five Other Bridges in the area. Instead, he chose to send his men across this narrow span directly into the face of Georgian sharpshooters on the hill directly above them. This was not only costly to human life but gravely delayed this entire flank operation, granting A.P. Hill enough time to return from Harper’s Ferry. See bibliography below.

Minor Oversights

Hindsight is always better than foresight. Nonetheless, the Union failed to take advantage of several opportunities that could have worked in their favor. Such as General Hooker not occupying a small mound to his right known as Allen’s Hill. Later in the morning, Confederate General Stuart placed artillery there and used it to inflict great damage on the troops of XII Corps.

"The rising ground gave admirable positions for artillery, and had these hills fallen into the possession of the Federals, Jackson’s divisions must have been driven back upon the Confederate centre. The historian Swinton blames Hooker because, after his first success in driving back Lawton’s three brigades to the Dunkard Church, he did not at once order up Mansfield’s corps, and occupy this ground. He says: There is a commanding eminence to the right of where Hooker’s flank rested, which would thus have been occupied; and as it is the key of the field, taking the woods with the outcropping ledges of limestone where Jackson’s reserves lay, its possession would, in all likelihood, have been decisive of the field. Hooker failed to perceive this."

Chapter X, The Life and Campaigns of Major-General J.E.B. Stuart

Summary

No one component of the above can be identified as the single reason for the enormous casualties at Antietam. It was instead, the combined effect of them all which contributed to the single largest number of dead, wounded, and missing during one day of battle in United States history.

The Battle of Antietam has been declared a Union victory because Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s vision of entering the northern States was halted. But it hardly seems a victory for Union General George B. McClellan because Antietam ended his military career. Perhaps the only true victor was the Dunker Church that opened its arms to the fighting men of both armies on the day following the battle. That Little Dunker Church still remains as a witness for peace.

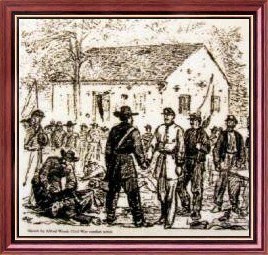

Sketch artists preceded battle photographers by many years. Brush and oil captured the pageantry of victory, horribly juxtaposed with the gruesome contortions of those slaughtered. From charcoal stick figures of cave paintings to the breathtaking murals of Antoine-Jean Gros. On the day following the battle, Alfred Waud stood before the Little Dunker Church and immortalized this peaceful scene of Union and Confederate soldiers talking with each other. It was paradoxical. Bewildering. Yet, strangely fascinating. |

|

The previous day they had fiercely struggled to kill each other on these very grounds, and now before Waud’s pencil they corporately mused over the hideous import of their actions. The Army of Northern Virginia would soon head west, crossing the wide Potomac river, while the Army of the Potomac would wait for Lincoln to clarify their mission. Weary men from each army would never forget this bloodiest day of battle, and how they finally enjoyed peace - in front of that Little Dunker Church. |

Photo Credits:

All modern photographs by Ronald J. Gordon © 1998, 2002. Other photographs, images, or reproductions are displayed with respect to intellectual property and compliance to all known Copyrights.

Bibliography:

Helen Ashe Hays, The Antietam and Its Bridges, New York and London: G.P. Putnam and Sons, 1910.

A complete listing of all resource materials involved in the production of this resource can be found at the bottom of the home document. Included are hard print literature, numerous maps, graphic images, and links to related web sites. Unlisted are numerous trips to the battlefield, visits to associated congregations, and personal interviews.