Acculturation of the Brethren in the Nineteenth Century

Written by Ronald J. Gordon ~ Published February, 1996 ~ Last Updated: September, 2020 ©

This document may be reproduced for non-profit or educational purposes only, with the

provisions that the entire document remain intact and full acknowledgement be given to the author.

any innovations of the Nineteenth Century irreversibly changed the Brethren who were mostly rurally situated, agriculturally minded, and moderately suspicious of outside influences. In the 1700’s and early 1800’s the Brethren easily managed to insulate themselves from the influences of American society due to their German sub-culture and rural location. What proved to complicate matters was the fact that while the more primitive rural Brethren generally abstained or refrained from technological innovations and more worldly social conventions, many of their urban counterparts were embracing both. Annual Conference (then called Annual Meeting), the denominational forum regularly became a factious arena where cultural and theological lines were clearly drawn between the more primitive Brethren (also called Old Orders, Ancient Brethren) and their progressive counterparts (also called The Progressives). This century dramatically restructured the social and theological framework of the German Baptist Brethren, and here are some of the contributing factors.

any innovations of the Nineteenth Century irreversibly changed the Brethren who were mostly rurally situated, agriculturally minded, and moderately suspicious of outside influences. In the 1700’s and early 1800’s the Brethren easily managed to insulate themselves from the influences of American society due to their German sub-culture and rural location. What proved to complicate matters was the fact that while the more primitive rural Brethren generally abstained or refrained from technological innovations and more worldly social conventions, many of their urban counterparts were embracing both. Annual Conference (then called Annual Meeting), the denominational forum regularly became a factious arena where cultural and theological lines were clearly drawn between the more primitive Brethren (also called Old Orders, Ancient Brethren) and their progressive counterparts (also called The Progressives). This century dramatically restructured the social and theological framework of the German Baptist Brethren, and here are some of the contributing factors.

ind possesses an elusive and mysterious quality: You can feel it but you can't see it. The direction of the slightest breeze can be determined by moistening a finger and turning it in the wind, because coolness from evaporation indicates the direction. This particular has often been metaphorically applied to moods and dispositions, e.i., political winds, winds of change, or winds of war. Elected officials often moisten their political fingers in order to determine the will of their constituents. People in different geographical environments or social class structures think differently. What is important to one group may not be given consideration by another group. A population might be culturally diverse in the same geographical locale. In colonial America, most of the population was concentrated along the Atlantic coastline, and their reasoning, logic, politics, and theology was generally uniform. As they migrated into new territories, belief systems gradually changed, due to new hardships and unexpected challenges. One of the most significant catalysts to encourage the movement of population in the history of American migration was the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. This action nearly doubled the size of the United States and energized an interest in moving west. In May of 1804, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set out to explore and map the new territory, and by 1850 a steady march of adventurers had created 2,170 miles of wagon ruts labeled the Oregon Trail. Railroads were also being constructed across the plains with a transcontinental hookup finally occurring in 1869 at Promontory Summit near Ogden, Utah. The nation was slowly moving west.

ind possesses an elusive and mysterious quality: You can feel it but you can't see it. The direction of the slightest breeze can be determined by moistening a finger and turning it in the wind, because coolness from evaporation indicates the direction. This particular has often been metaphorically applied to moods and dispositions, e.i., political winds, winds of change, or winds of war. Elected officials often moisten their political fingers in order to determine the will of their constituents. People in different geographical environments or social class structures think differently. What is important to one group may not be given consideration by another group. A population might be culturally diverse in the same geographical locale. In colonial America, most of the population was concentrated along the Atlantic coastline, and their reasoning, logic, politics, and theology was generally uniform. As they migrated into new territories, belief systems gradually changed, due to new hardships and unexpected challenges. One of the most significant catalysts to encourage the movement of population in the history of American migration was the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. This action nearly doubled the size of the United States and energized an interest in moving west. In May of 1804, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set out to explore and map the new territory, and by 1850 a steady march of adventurers had created 2,170 miles of wagon ruts labeled the Oregon Trail. Railroads were also being constructed across the plains with a transcontinental hookup finally occurring in 1869 at Promontory Summit near Ogden, Utah. The nation was slowly moving west.

Included in this westward ambulation was a small Brethren Migration, first traveling on the Ohio River from Pittsburgh into Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. Eventually the lure of cheap land and freedom encouraged them to move all the way to the Pacific coast where they established several congregations. So heavily did the Brethren populate the mid-west and far-west that in 1822, Annual Meeting was first held to the west of the traditional thin Atlantic coastline. In the next fifty years, cultural adjustments for the Brethren were profoundly challenging as they felt the social effects of different winds. Brethren in the east were close knit whereas their western counterparts were scattered. Harmony between churches was comfortably maintained in the east, but western Brethren were separated from each other by hundreds of miles. In some cases, they were too few in number to even build a church. Western congregations generally lacked economic resources while eastern Brethren enjoyed financial stability. Easterners in general were able to communicate news quickly, but sparsely populated westerners received news intermittently. Fellowship, affirmation, consensus, and bonding was lacking in the west. Conversely, eastern Brethren relished these particulars. Although basic doctrines and practices remained somewhat unaffected during the initial migrations, the Brethren were incrementally digressing into two entirely different worlds, and denominational conversation soon gave evidence of these different winds. Eastern Brethren were strongly aligned through tradition, supervised by the Eldership and predictably looked to Annual Meeting as a place to settle matters of discord. Western Brethren were more loosely aligned through a common mystic of survival in a harsh and unforgiving territory, and did not esteem Annual Meeting with the same degree of passion as their eastern counterparts.

Concerned voices appealed to Annual Meeting for a remedy to the situation. One such appeal for unity was for the creation of denominational literature that would serve as a central platform for the dissemination of news and the discussion of ideas. Although separated by great distances, Brethren literature could bridge the geographical and social gap with articles, news, and human interest stories. However, these publications only shifted the location of the dialog. Additionally, new winds began to move an aggregate body into distinct groups: liberal and conservative, traditional and progressive, innovative and plain.

enry Kurtz was born in Germany in 1796 with aspirations for the ministry. After emigrating to America, he entered the Luther Synod and received his first pastorate in Pennsylvania. While studying the Bible he became convinced that faith was an essential part of baptism. A novel opinion for a Lutheran, and this position soon led to his excommunication. He moved to Ohio where he later met and joined the Brethren. Gradually he became deeply involved in roles of leadership. In a few years, Kurtz served as pastor, ordained elder, and writing clerk of Annual Meeting; a position which he held for almost twenty years. One reason being that he could intimately converse in both German and English, and the Brethren were in the midst of changing from exclusive use of German to English. The concern for denominational literature found its champion in Kurtz who had briefly attempted to publish a church paper while a Lutheran minister. A question presented to Annual Meeting in 1850 concerning denominational literature reawakened his enthusiasm for publishing, and he began to set in motion the publication of the first Brethren periodical.

enry Kurtz was born in Germany in 1796 with aspirations for the ministry. After emigrating to America, he entered the Luther Synod and received his first pastorate in Pennsylvania. While studying the Bible he became convinced that faith was an essential part of baptism. A novel opinion for a Lutheran, and this position soon led to his excommunication. He moved to Ohio where he later met and joined the Brethren. Gradually he became deeply involved in roles of leadership. In a few years, Kurtz served as pastor, ordained elder, and writing clerk of Annual Meeting; a position which he held for almost twenty years. One reason being that he could intimately converse in both German and English, and the Brethren were in the midst of changing from exclusive use of German to English. The concern for denominational literature found its champion in Kurtz who had briefly attempted to publish a church paper while a Lutheran minister. A question presented to Annual Meeting in 1850 concerning denominational literature reawakened his enthusiasm for publishing, and he began to set in motion the publication of the first Brethren periodical.

The Gospel Visitor was first issued in 1851 from a hand-press located on the second floor of a spring house on a small farm in Ohio. Its appearance was professional and noteworthy considering the humbleness of its origin. Although not recognized as an official voice of the denomination because of it’s personal emanation, delegates to the Annual Meeting of the same year decided that it’s worthiness should be judged by all Brethren congregations until next year. James Quinter became assistant editor in 1856 with Henry Holsinger soon joining the team. Holsinger wanted to produce a weekly paper, and started the Christian Family Companion. It contained free expression of ideas from individual members which could then be read by the larger community, a new concept for the Brethren and a primal form of an Internet list server. Holsinger was more progressive than most Brethren and continued along several avenues to suggest innovations such as Sunday School, foreign missions, and revival meetings. Correlative voices soon took advantage of the opportunity to advocate disuse of the distinctive plain dress and the supremacy of the Elder dominated Annual Meeting (Conference). The larger segment of Brethren were now torn between the Progressive agenda and those Traditionals who wanted to maintain status quo or restrict innovation.

The Gospel Visitor and Christian Family Companion were eventually merged, adopting the title The Primitive Christian. Quinter became the chief editor and Kurtz devoted his time to working on a Brethren Encyclopedia which first appeared in 1867. The Primitive Christian later absorbed the Pilgrim in 1876, another weekly paper issued by H.B. & J.B. Brumbaugh from James Creek, Pennsylvania. In the same year, J.T. Myers and L.A. Plate started the Brethren’s Messenger from Germantown, Pennsylvania and then moved it to Lanark, Illinois with a new title, Brethren at Work. In 1883, these two papers were merged to form the Gospel Messenger. The word Gospel was dropped from the title in January 1965; and it’s frequency of publication changed from weekly to monthly. James Quinter and H.B. Brumbaugh worked as co-editors. Messenger is still published by the General Offices at Elgin, Illinois.

As the free exchange of ideas manifested itself in Brethren books and periodicals, this exposure forced the Brethren to acknowledge the influence and values of the larger world and contributed to the widening gulf between progressives and conservatives. Before the appearance of Brethren literature, there was no published denominational voice except the minutes of decisions from Annual Conference. Until the emergence of these publications, the eldership had a firm grip on any denominational voice because they controlled the proceedings of Annual Conference. Now, the general membership would also have the opportunity to voice their personal opinions about church life or society through these periodicals. Compounding the issue for the Elders was the fact that each publication was not officially recognized by the denomination. These papers were the inspiration of lay persons, entrepreneurial undertakings without any outside controls on content or expression. Each editor was relatively free to make his publication become what he envisioned it should be, although there would naturally have been an environment of discretion on the part of the editor, if he wanted his paper to gain wide acceptance within the denomination.

In a modern world of instant communication one might question why publications would have had a deleterious effect on some Brethren. It can be understood only if we strive to appreciate the mind set of the time. Communication was not the issue but its invasion of a sub-culture that viewed outside influences with suspicion. For example, if the controlling party of Annual Conference made specific decisions on matters of faith and practice, members now had an opportunity to voice their opinions about these decisions. The widespread reading of their opinions in these new publications also had a lobbying effect. Many other ingredients contributed to the attrition of the Brethren sub-culture, particularly matters of nonconformity. Usually this topic focused on clothing and apparel but it was a much larger issue that involved a direct challenges to historic Brethren understandings, such as decisions about nonparticipation in war, plus a whole new issue and subsequent call for professionalism in the ministry.

rethren were a sequestered people from the time of their beginnings in Schwarzenau, Germany, under a hostile church-state environment. Forced into isolation because of their convictions and unwaveringly pursued by authorities, the Brethren naturally resisted conformity to the outside world. Although colonial liberty spared them from governmental harassment, their language and culture impeded their infusion with the larger surrounding culture. The name Germantown (town of Germans) represents their hesitancy to assimilate with others of foreign descent. Perhaps, the Hacker affair in Krefeld which precipitated Brethren emigration to America continued to govern their isolationism. Mostly living on farms or in rural areas helped to preserve their nonconformity. For dress-up events, men typically wore plain dark outer clothing with few buttons, white shirt without a tie, plus the obligatory large broad-brimmed hat. Folded up labels then created an open square just below the chin. Beards with or without mustache, but never mustache alone, because it reminded the Brethren of the horse-mounted European Cavalry Officers.

Women typically wore the

Triangular Cape

or bib that covered the upper-waist both front and back, beginning at the outer crown of each shoulder and converging to a point near the center of the waist. Bonnets or coverings were strictly enforced for any women or girl who was a member of the church.

rethren were a sequestered people from the time of their beginnings in Schwarzenau, Germany, under a hostile church-state environment. Forced into isolation because of their convictions and unwaveringly pursued by authorities, the Brethren naturally resisted conformity to the outside world. Although colonial liberty spared them from governmental harassment, their language and culture impeded their infusion with the larger surrounding culture. The name Germantown (town of Germans) represents their hesitancy to assimilate with others of foreign descent. Perhaps, the Hacker affair in Krefeld which precipitated Brethren emigration to America continued to govern their isolationism. Mostly living on farms or in rural areas helped to preserve their nonconformity. For dress-up events, men typically wore plain dark outer clothing with few buttons, white shirt without a tie, plus the obligatory large broad-brimmed hat. Folded up labels then created an open square just below the chin. Beards with or without mustache, but never mustache alone, because it reminded the Brethren of the horse-mounted European Cavalry Officers.

Women typically wore the

Triangular Cape

or bib that covered the upper-waist both front and back, beginning at the outer crown of each shoulder and converging to a point near the center of the waist. Bonnets or coverings were strictly enforced for any women or girl who was a member of the church.

Although styles varied from home to home and congregation to congregation, the guiding principles of garment construction were simplicity, plainness, and modesty. Beside the functionality of covering the body, clothing also serves to convey inner motives and subtleties. Colors, trimmings, and ornaments enhance these predispositions. Bright red transmits a different message to others than dark blue. An over abundance of jewelry projects something far different than the absence of it. In the early part of the century, most garments were made at home where style and appearance was under family control. Towards the middle to latter part of the century, factory produced garments were more readily available and cheaper. The values of the outside world could now be displayed on the wearer and likewise influence the observer. As more Brethren started to wear factory made clothing, the gulf would gradually widened between those who accepted or resisted acculturation.

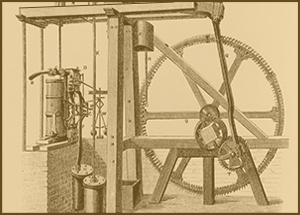

he Industrial Revolution began in Great Britain soon after the invention of the steam engine, and especially it’s lucrative improvement in 1760. For the next one hundred years, life in England and America would dramatically change. Social and economic factors would greatly affect the Brethren. In America the Industrial Revolution may be described as the application of power-driven machinery to the manufacturing sector, but in England it largely meant developing machinery that augmented the worker. No shortage of skilled labor existed in Britain. Mechanization did not replace large segments of the work force. Instead, machinery helped English factory workers and talented artisans become more precise. Colonial America was sparsely populated and machinery allowed fewer laborers to accomplish even more. As industrialization spread throughout America, population began shifting from the country to the cities where large factories promised higher and more steady wages. It might also be called a Demographic Revolution as well. About nine out of ten people lived in rural America. People raised most of their food and built many of their tools. Most people did not own a clock because they didn't need to leave home each day to work somewhere else. Life was regulated by the rising and setting of the sun.

It’s hard for many people to imagine a time when there were no electric lights, recorded music, television, or automobiles. Families were more tightly bonded because unless you could walk, visiting meant harnessing a horse and hitching a carriage. People stayed at home. Children spent much of their evening reading what few books were available. Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin in 1793, which mechanized the removal of the seeds from the fibers and made cotton incredibly cheap, plus it was much stronger than wool. Until this time, many garments had been made of wool. People gladly exchanged their scratchy, fungus-filled woolens for lighter and stronger ones made of cotton.

he Industrial Revolution began in Great Britain soon after the invention of the steam engine, and especially it’s lucrative improvement in 1760. For the next one hundred years, life in England and America would dramatically change. Social and economic factors would greatly affect the Brethren. In America the Industrial Revolution may be described as the application of power-driven machinery to the manufacturing sector, but in England it largely meant developing machinery that augmented the worker. No shortage of skilled labor existed in Britain. Mechanization did not replace large segments of the work force. Instead, machinery helped English factory workers and talented artisans become more precise. Colonial America was sparsely populated and machinery allowed fewer laborers to accomplish even more. As industrialization spread throughout America, population began shifting from the country to the cities where large factories promised higher and more steady wages. It might also be called a Demographic Revolution as well. About nine out of ten people lived in rural America. People raised most of their food and built many of their tools. Most people did not own a clock because they didn't need to leave home each day to work somewhere else. Life was regulated by the rising and setting of the sun.

It’s hard for many people to imagine a time when there were no electric lights, recorded music, television, or automobiles. Families were more tightly bonded because unless you could walk, visiting meant harnessing a horse and hitching a carriage. People stayed at home. Children spent much of their evening reading what few books were available. Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin in 1793, which mechanized the removal of the seeds from the fibers and made cotton incredibly cheap, plus it was much stronger than wool. Until this time, many garments had been made of wool. People gladly exchanged their scratchy, fungus-filled woolens for lighter and stronger ones made of cotton.

The years between 1800 and 1850 would begin to change how people lived for this nation experienced spectacular growth in population, land acquisition, wealth, and the rise of a middle class. In just the first half of the Nineteenth Century these innovations appeared: steam locomotive (1804), photography (ca. 1826), grain reaper (1831), gas refrigeration (1834), telegraph (1836), pneumatic tire (1845), sewing machine (1846). These were soon followed by the internal-combustion engine, dynamite, typewriters, telephones, incandescent light, automobiles, the safety elevator, and skyscrapers. Immediately following the Civil War, the reunited United States emerged as an industrial giant. Whole new industries appeared, such as the refining of petroleum and the manufacturing of steel. Railroad delivered cheaper goods in greater quantities to even remote parts of the country. This produced a new class of wealthy industrialists and a prosperous middle class. The growing proliferation of new manufactured products constantly tempted the Brethren to abandon their reclusive sub-culture which had prided itself on plainness and simplicity.

Of all the innovations that arrived during this century, one might suggest the following four as the more significant. They were the early portals which allowed the others to pass through. Without their early presence, the Industrial Revolution would have been either impossible or so gradual in arriving that one would be significantly hard pressed to describe it as a revolution.

Steam Power

Without the creation of factories driven by steam power, the Industrial Revolution would have been nearly impossible. Steam mechanisms are as old as Hero of Alexandria, Egypt (60 B.C.) but they were either social novelties or contraptions that performed small-scale work. Thomas Savery and Thomas Newcomen constructed the first working steam engines in England, around 1700. They were sadly inefficient and nearly impractical on a large scale because they required enormous amounts of water. It would be the improvements made to their engine by James Watt in 1760, that made steam power cheaper and more practical. Watt added a separate condensing chamber which immensely cut down on the amount of wasted steam in the main cylinder. Additionally, he added sun-and-planet wheels to convert reciprocal motion into rotary motion, plus a centrifugal governor to regulate the speed. These improvements made the steam engine more efficient and opened the door for the creation of large scale factories producing cheaper and greater quantities of goods.

Iron Founding

The Iron industry has been with us since, well, the Iron Age of prehistoric times, but it was not profitable or large scale until significant improvements were made such as the use of coke instead of charcoal around 1750. It takes lots of carbon to extract oxygen and impurities from iron ore and the main source of carbon was charcoal that came from the burning of trees. It requires about 100 kg of charcoal to make 1 kg of steel. Woodland was being consumed at incredible rates. When coal is converted into coke it withdraws many of the impurities from iron ore as gases or liquids and is far more acceptable for smelting. The large scale production of iron and later steel would revolutionize the construction and industrial landscape.

Textiles

Steam power made it possible to drain water from mines and permit the English miner to go deeper and extract more coal than previously thought possible. The production of more coal spun off other industries such as textiles. Early cotton mills not constructed next to rivers were powered by horses, the first in Beverly, Massachusetts in 1787 by John Cabor and his brothers. They traveled to England and did their best to memorize how steam powered the textile industry. A proliferation of cotton mills soon led to the creation of mill towns. People seeking employment flocked to these settlements. Water powered cotton mills still remained somewhat competitive with steam in New England. The Amoskeag Manufacturing Company of New Hampshire started in 1831 and became the largest cotton textile operation in the world, having about 30 mills and not quite 18,000 workers. Cotton mills in the Carolina’s prospered. Their owners dominated the economy and politics of the region. One reason that New England mills gradually went bankrupt and the Southern States became more profitable was because transportation costs in the deep south were negligible. Cotton could be harvested, processed, and made into fabric in the same geographical area. Textiles produced enormous wealth which fueled other segments of the Industrial Revolution.

Portland Cement

At first, one might not think of this innovation as a significant part of the Industrial Revolution, but nonetheless, it led to the erection of taller and safer buildings that would house or employ more people in a much smaller area. It might be considered a silent partner of the Industrial Revolution. The Babylonians used clay as their bonding substance. The Egyptians used lime and gypsum. The Romans mixed slaked lime with a type of volcanic ash. But cement of the ancient world was not consistent, predictable, or enduringly strong. When Joseph Aspdin invented Portland Cement in 1824, the world had a much better bonding material that was produced according to a special formula of carefully proportioned chemicals that allowed engineers to change its properties and accurately predict the results. It was a slow setting cement and extremely strong. A more predictable and stronger cement under-girded the construction industry that produced larger buildings for more people. The introduction of steel in building construction would later prove to create another architectural revolution with the erection of the skyscraper.

The use of some “new things or new ways” precipitated heated debate at Annual Conference that was not always resolved the same year. The installation of lightning rods was one of the first to initiate controversy in the Brethren camp, since many regarded them a lack of faith in God’s providential care. This question was presented to Annual Conference over a period of several years with the final decision “advising” the Brethren to neither install or remove them, but place their trust in God; however, it also pleaded with members to accept each others individual choice. This was a surprising display of tolerance at a time wen Brethren were often viewed as dogmatic authoritarians. Other issues would also make the journey to Annual Conference such as carpeting on floors, photographs, life insurance, and incurring debt with interest. The rural and more conservative mind often viewed these innovations with immediate suspicion. Perhaps, because the very ownership of gadgets and seemingly useless devices was foreign to a culture whose European period was typified by constant migration to avoid persecution. When death becomes an imminent reality, possessions often have little meaning. In the new world, many Brethren were involved with farming, a simplistic life style that had existed for thousands of years without numerous devices and gadgetry. Additionally, the possession of certain machinery naturally invites a controlling interest from the factory which produces it. In other words, the aversion to a device may not be the device itself, but the fear of one’s life being later heavily influenced by outside forces.

s one of the three historic peace advocate churches, the Church of the Brethren resists any involvement in war, the bearing of weapons, or the rendering of assistance to entities involved in the killing of human beings. However, this century introduced a war that challenged the Brethren position. The Civil War impacted this country, perhaps more so than any other single event because of the debilitating effects of internal conflict when brother fights against brother. Additionally, the ugliness of slavery demanded recognition, the immense economic aftermath changed the very structure of the federal government, and the death of President Lincoln created a national wound. The great majority of Brethren did not enlist, and many who did, refused to kill. Nonparticipant s paid heavy files or went to prison while others fled and resettled elsewhere. The general mood of the nation, resting on the momentum of the Revolutionary War did not yet recognize pacifism. Still fixed in the national conscience was the Minute Man who left field & farm to serve his country, and figures such as Patrick Henry who was immortalized for his declaration of“give me liberty, or give me death." The inconsistency of Brethren involvement in the Civil War began a process of debate within the denomination that had not previously existed. Pacifism had its roots in Anabaptist thought and was for the Brethren a given understanding. Why then did some Brethren leave their pacifist heritage for the battlefield? Was the Civil War unique among hostilities? Why the sudden tolerance of military participation? In his book,“Studies in Brethren History," page 268, Floyd Mallott shares this interesting observation.

s one of the three historic peace advocate churches, the Church of the Brethren resists any involvement in war, the bearing of weapons, or the rendering of assistance to entities involved in the killing of human beings. However, this century introduced a war that challenged the Brethren position. The Civil War impacted this country, perhaps more so than any other single event because of the debilitating effects of internal conflict when brother fights against brother. Additionally, the ugliness of slavery demanded recognition, the immense economic aftermath changed the very structure of the federal government, and the death of President Lincoln created a national wound. The great majority of Brethren did not enlist, and many who did, refused to kill. Nonparticipant s paid heavy files or went to prison while others fled and resettled elsewhere. The general mood of the nation, resting on the momentum of the Revolutionary War did not yet recognize pacifism. Still fixed in the national conscience was the Minute Man who left field & farm to serve his country, and figures such as Patrick Henry who was immortalized for his declaration of“give me liberty, or give me death." The inconsistency of Brethren involvement in the Civil War began a process of debate within the denomination that had not previously existed. Pacifism had its roots in Anabaptist thought and was for the Brethren a given understanding. Why then did some Brethren leave their pacifist heritage for the battlefield? Was the Civil War unique among hostilities? Why the sudden tolerance of military participation? In his book,“Studies in Brethren History," page 268, Floyd Mallott shares this interesting observation.

"There is a direct relationship between participation in government and participation in military service. In monarchical Europe the question of participation in government-and the attempt at directing society-did not occur. Only in the New World with its theory of democratic participation could the question be raised."

If Mallott’s observation is valid, then Brethren involvement in national government could be antithetical to it’s pacifistic heritage. Yet if abstention from politics is desirable, how then may Brethren participate in the“directing of society?" The next century would experience two world conflicts with a higher percentage of Brethren involved in each. The modern Church of the Brethren maintains its official appellation of a Historic Peace Church, yet it’s members continue to struggle with these questions:“Is it permissible for a Christian to kill another human being? Is it consistent with the gospel to assist those who kill? What is an acceptable level of involvement in national politics?...or the military?"

ree ministry was observed in Brethren congregations so as to keep the allegiance of the speaker in harmony with the Holy Spirit and not diminished by financial conflicts with the congregation. Ministers did not receive a salary, wage, or stipend for their spiritual contributions. For this reason it was not uncommon for a church to have several ministers who earned a living from a separate occupation. There were few, if any, salaried Brethren ministers during the first half of the Nineteenth Century. Some were farmers while others were skilled craftsmen and various methods were used in their selection. The candidate would then meet in a closed room for an interview with the Elders, because only the latter understood the actual sentiment and plurality of congregations (see expanded below). Installation began a process that would eventually advance them through Three Degrees of the ministerial office. A first degree minister could preach a single sermon, or with permission, conduct the entire worship service. Second degree ministers were authorized to perform a baptism and conduct a love feast. Third degree ministers or elders had attained the highest degree, and were charged with the spiritual welfare of entire congregations. Usually there were a few years of apprenticeship in each office before one may attain the next higher degree. Several ministers would serve a congregation, so as not to burden any one person with too much responsibility. It was not uncommon for larger Brethren churches to have six to eight ministers with three of them preaching a sermon each Sunday morning. The prevailing concept deemed the ministerial role as a divine obligation that should be liberated from temporal entanglements. Remuneration was perceived as merchandising the gospel. It was also feared that paid ministers would become merchants with a greater proclivity towards satisfying the consumer with less intensive sermons. Unpaid ministers with sole allegiance to God might be more inclined to regularly preach sermons that “step on toes” and preserve the fundamentals of the faith, especially the historic traditions of Brethrenism.

ree ministry was observed in Brethren congregations so as to keep the allegiance of the speaker in harmony with the Holy Spirit and not diminished by financial conflicts with the congregation. Ministers did not receive a salary, wage, or stipend for their spiritual contributions. For this reason it was not uncommon for a church to have several ministers who earned a living from a separate occupation. There were few, if any, salaried Brethren ministers during the first half of the Nineteenth Century. Some were farmers while others were skilled craftsmen and various methods were used in their selection. The candidate would then meet in a closed room for an interview with the Elders, because only the latter understood the actual sentiment and plurality of congregations (see expanded below). Installation began a process that would eventually advance them through Three Degrees of the ministerial office. A first degree minister could preach a single sermon, or with permission, conduct the entire worship service. Second degree ministers were authorized to perform a baptism and conduct a love feast. Third degree ministers or elders had attained the highest degree, and were charged with the spiritual welfare of entire congregations. Usually there were a few years of apprenticeship in each office before one may attain the next higher degree. Several ministers would serve a congregation, so as not to burden any one person with too much responsibility. It was not uncommon for larger Brethren churches to have six to eight ministers with three of them preaching a sermon each Sunday morning. The prevailing concept deemed the ministerial role as a divine obligation that should be liberated from temporal entanglements. Remuneration was perceived as merchandising the gospel. It was also feared that paid ministers would become merchants with a greater proclivity towards satisfying the consumer with less intensive sermons. Unpaid ministers with sole allegiance to God might be more inclined to regularly preach sermons that “step on toes” and preserve the fundamentals of the faith, especially the historic traditions of Brethrenism.

Depending on the location and size of the congregation, ministers were generally selected or elected along the following scheme. As the congregation sensed the need for an additional minister, each member would privately spend time considering which of the young men of the congregation would be most suited for the office. Elders from nearby congregations would convene a special day of examination to question members on their choice. One by one each member would go into a private room with the elders and respond to questions regarding their preference. There were no ballots or nominations, for this was selection by plurality. After reviewing the entire membership, the elders would emerge to inform the congregation of their decision. This practice was later challenged because it may allow a minority of voices to select a minister. During the last half of the century, new voices called for open elections with ballots and nominations so that any selection would be consequential to a majority of the congregation. Traditional voices did not like the democratic scheme because it appeared to exclude the guidance of the Holy Spirit in concert with the eldership. Voices of change were further reminded that when elders pronounced the winning candidate, they would then ask the congregation for unanimous consent which did require a majority opinion.

As times changed, so did the role of the pastor. Ministers generally did not receive advanced education, but relied on their own study of the Bible, as well as personal experiences in the vast arena of life. Rural oriented Brethren from a slower pace began moving to cities, and experienced the faster pace of city life which required the pastor to assume a more 'executive type' role within the church. Instead of congregations personally involved in witnessing, programs were instituted by churches to transfer money to other agencies with specialized resources for witnessing. As the identity of the church changed, so did the role of its pastor. Instead of the more traditional role of preacher, the minister began to assume the role of program director. This new role required the pastor to be more of an executive than a layman who would 'stall the horses and put on the preach'n hat.' Toward the end of the century, the Brethren founded Colleges which produced a more educated candidate for ministry and missionary work.

As increasing numbers of ministers graduated from these schools, many congregations openly expressed a desire for an educated pastor instead of the crude rural preacher, sometimes referred to as a “Dumb Dunkard” was the common terminology. The traditional Brethren contended for an Eldership controlled selection process, arguing that elders in harmony with the Holy Spirit was the most reliable process. Younger men desired the 'nomination & ballot' method, so as to remove control from Elders in closed rooms. Ministers with education and occupational preparation became the requisite of many congregations, and with an increase in ministers assuming professional status, congregations gradually modified their individual responsibility to the community because they began transferring money to other agencies that would perform these duties. Additionally, single role ministers serving as pastors needed more training to facilitate their congregations. Education was becoming a necessary part of ministerial preparation and a formal school to educate the pastor for the modern congregation became inevitable. In 1905, Albert C. Wieand and Emanuel B. Hoff founded Bethany Bible School in a private home in Chicago after learning that Brethren ministerial candidates were planning to enroll in the nearby Moody Bible School. In spite of continuing opposition to higher education, the Van Buren street campus of Bethany Biblical Seminary was garnered by the Church of the Brethren in 1925. After more than forty years of service, a new facility was constructed west of the Chicago area near the community of Oak Brook, and the name was later changed to Bethany Theological Seminary. The school moved once again to Richmond, Indiana in 1994 to share the campus of the Earlham School of Religion. As the Nineteenth Century was drawing to a close, professional education and Brethren ministerial preparation were becoming synonymous.

homas Jefferson was elected President of the United States of America in 1800, a very intellectually gifted man with an extraordinary vision for the new republic. Jefferson had earlier penned the Declaration of Independence during the colonial period and guided many voices crying for freedom. Now as President, Jefferson would guide this same nation into a new century, an interval that would prove to be a time of immense social and technological change. In 1779, Jefferson issued A Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge, a proposal to the Virginia Assembly suggesting that the state pay for the education of boys and girls for a minimum of three years. Although it failed to acquire enough votes, this paper gives us a clear idea of his perspective on education. Jefferson believed that an educated populace was the best guarantee of liberty. By studying history, people would understand how governments become corrupt and tyranny begins. During the election of 1800, while his own party was in turmoil and conflict, Jefferson wrote in a private letter: “I have sworn upon the altar of God, eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.” He perceived that a good education and intellectual awareness were the major guardians of a free society. Although older universities such as Harvard, Yale, and Dartmouth had been in operation for decades, nineteen new colleges received their charters from 1782 until 1802, and each institution is still in operation. In 1819, ex-president Thomas Jefferson became instrumental in the chartering of the University of Virginia at Charlottesville, three miles west of his estate at Monticello, with additional devotion to planning the grounds, buildings, and curriculum. Basic education in colonial America was generally composed of reading, writing, arithmetic, and learning poems. Textbooks and paper was often scarce, so boys and girls frequently shared resources and memorized as much as possible. Basic materials usually consisted of a Primer, the Bible, and a Hornbook. Colonial education was usually for white students only. Non-white children were not privileged to attend school except in the rarest circumstance. In a society before radio, television, and computer games, most youth spent their evenings reading, much of the time from the Bible.

homas Jefferson was elected President of the United States of America in 1800, a very intellectually gifted man with an extraordinary vision for the new republic. Jefferson had earlier penned the Declaration of Independence during the colonial period and guided many voices crying for freedom. Now as President, Jefferson would guide this same nation into a new century, an interval that would prove to be a time of immense social and technological change. In 1779, Jefferson issued A Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge, a proposal to the Virginia Assembly suggesting that the state pay for the education of boys and girls for a minimum of three years. Although it failed to acquire enough votes, this paper gives us a clear idea of his perspective on education. Jefferson believed that an educated populace was the best guarantee of liberty. By studying history, people would understand how governments become corrupt and tyranny begins. During the election of 1800, while his own party was in turmoil and conflict, Jefferson wrote in a private letter: “I have sworn upon the altar of God, eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.” He perceived that a good education and intellectual awareness were the major guardians of a free society. Although older universities such as Harvard, Yale, and Dartmouth had been in operation for decades, nineteen new colleges received their charters from 1782 until 1802, and each institution is still in operation. In 1819, ex-president Thomas Jefferson became instrumental in the chartering of the University of Virginia at Charlottesville, three miles west of his estate at Monticello, with additional devotion to planning the grounds, buildings, and curriculum. Basic education in colonial America was generally composed of reading, writing, arithmetic, and learning poems. Textbooks and paper was often scarce, so boys and girls frequently shared resources and memorized as much as possible. Basic materials usually consisted of a Primer, the Bible, and a Hornbook. Colonial education was usually for white students only. Non-white children were not privileged to attend school except in the rarest circumstance. In a society before radio, television, and computer games, most youth spent their evenings reading, much of the time from the Bible.

The move towards higher education in America was a protracted experience, that steadily gained momentum in the first half of the Nineteenth Century. The first parochial school was founded in 1809 near Baltimore by Elizabeth Ann Seton. Bostons English High School opens in 1821 with 102 students and in 1827, Massachusetts required every town of 500 families to support a high school. Emma Willard School was founded at the Troy Female Seminary near Troy, New York in 1821, by educator Emma Hart Willard, 34, to prove that women can master subjects such as mathematics and philosophy. In the next ten years, many towns in New England mandated elementary education.

igher education was not a significant issue for the German Baptist Brethren until the latter half of the century. Determined to preserve their rural German sub-culture, the Brethren modestly resisted the concept of higher education at the family level for two principal reasons: they were a hard working people immediately concerned with making a living and viewed formal education as a luxury, additionally there was a significant fear that outside social influences, especially of campus life, would alter the spiritually established principles of their young men and women. Minutes from Annual Meeting fail to exhibit a formal denominational prohibition to public education, but acceptance of college education was resisted from the first petition in 1831 until the middle of the century when a complete reversal occured in 1858. This was predictable because so many Brethren were either attending or teaching in colleges and universities. Leading the movement to higher education were the more progressive Brethren who believed that their youth, and the denomination as a whole, may quickly fall behind other religious bodies who openly supported the idea of colleges and seminaries. During the last half of the Nineteenth Century, literally hundreds of colleges and higher institutions of learning were founded across the American landscape: Bryn Mawr, Brigham Young, Clemson, Cornell, Drexel, Florida State, Gallaudet, Kansas State, La Salle, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Mississippi State, Ohio State, Purdue, Rutgers, Seton Hall, Texas A&M, Ursinus, Vassar, and Wheaton to name only a few. Theological seminaries were also being established during this century: Princeton was founded by the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in 1812, Union Theological Seminary of New York City in 1836, the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary of the Southern Baptist Convention was founded in 1859, and the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia was founded in 1864.

igher education was not a significant issue for the German Baptist Brethren until the latter half of the century. Determined to preserve their rural German sub-culture, the Brethren modestly resisted the concept of higher education at the family level for two principal reasons: they were a hard working people immediately concerned with making a living and viewed formal education as a luxury, additionally there was a significant fear that outside social influences, especially of campus life, would alter the spiritually established principles of their young men and women. Minutes from Annual Meeting fail to exhibit a formal denominational prohibition to public education, but acceptance of college education was resisted from the first petition in 1831 until the middle of the century when a complete reversal occured in 1858. This was predictable because so many Brethren were either attending or teaching in colleges and universities. Leading the movement to higher education were the more progressive Brethren who believed that their youth, and the denomination as a whole, may quickly fall behind other religious bodies who openly supported the idea of colleges and seminaries. During the last half of the Nineteenth Century, literally hundreds of colleges and higher institutions of learning were founded across the American landscape: Bryn Mawr, Brigham Young, Clemson, Cornell, Drexel, Florida State, Gallaudet, Kansas State, La Salle, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Mississippi State, Ohio State, Purdue, Rutgers, Seton Hall, Texas A&M, Ursinus, Vassar, and Wheaton to name only a few. Theological seminaries were also being established during this century: Princeton was founded by the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in 1812, Union Theological Seminary of New York City in 1836, the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary of the Southern Baptist Convention was founded in 1859, and the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia was founded in 1864.

A continued emphasis on spiritual and community attributes instead of more worldly education gave the Brethren a primitive stereotype which often elicited the phrase - Dumb Dunkard. It was an undeserved phrase which troubled some Brethren and propelled them to the point of creating schools that would educate their youth into a more refined citizenry. They wanted to erase that plebeian caricature once and for all, while others felt comfortable in the pursuit of spiritual education without regard to worldly appellations. Progressives wanted their youth to excel in academia, while others noted that ignorant Galilean fishermen turned the world upside down without a formal education, that God seeks the lowly to confound the wise: But God hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise; and God hath chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty; And base things of the world, and things which are despised, hath God chosen, yea, and things which are not, to bring to nought things that are: That no flesh should glory in his presence" 1 Corinthians 1:27-29. Tensions arose which created strong feelings about the course of the denomination. Factions evolved that later contributed to the Schisms of 1881-1882. Momentum for the establishment of Brethren colleges and universities was not a denominationally coordinated effort, but rather an interspersed energy rising from the vision of unrelated individuals at different times in various geographical locations, starting with Juniata College in 1876 and ending with Elizabethtown College in 1899. Annual Meeting uniformly declined to assume any degree of ownership in the colleges and further stipulated that the word Brethren should not be included in the school label.

Bridgewater College evolved from the former Spring Creek Normal School, which was founded in 1880 under the leadership of Daniel Flory. The school was originally located at Spring Creek, Virginia, but moved a few miles east to Bridgewater in 1882, just in time for the fall semester. It was incorporated by the State of Virginia in 1884 and the label changed to Bridgewater College in 1889 after revising its charter. Full accreditation as a four-year college by the Virginia State Board of Education came in 1916. A renovation began in the early 1960s that resulted in a larger enrollment, more buildings, off-campus internships, and a stronger athletic program. It is a co-educational institution with an enrollment near 1,000.

Juniata College is the oldest of the six colleges that are affiliated with the Church of the Brethren. It was the vision of three central Pennsylvania men of the Brumbaugh family who steadfastly advocated the establishment of a Brethren institution of higher education. Martin Brumbaugh was later elected governor of Pennsylvania (1915-19). The college officially opened for classes on April 17, 1876 as the Huntingdon Normal School. Its label was changed to Brethren’s Normal College two years later, and then finally to Juniata College in 1894 (from the nearby Juniata River). The school received full accreditation from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1896, and is a co-educational institution with an enrollment near 1,300.

Elizabethtown College officially opened for classes on November 13, 1900, at the corner of South Market and Bainbridge streets in Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania. Elders of the German Baptist Brethren of Pennsylvania Eastern district were invited in 1898 to attend a meeting for the expressed purpose of founding an institution of higher education, and a committee subsequently recommended Elizabethtown as their choice location. The school was moved to the east side of town in January of the following year, and came under ownership of the Eastern Pennsylvania district of the Church of the Brethren in 1917. For the first twenty years it also operated an academy for high-school students, and received accreditation for issuing baccalaureate degrees from the State Council on Education in 1921. Several building and renovation initiatives during the 1950-1960s greatly increased the size of the campus. This strengthened its academic program, which offers study in almost forty major pursuits. It is a co-educational institution with an enrollment near 1,500 (largest of the six colleges).

La Verne, University of was founded by members of the Church of the Brethren under the name of Lordsburg College in 1891. The Church of the Brethren Pacific Southwest District took over the administration of the school in 1908, and the name of the school was changed to La Verne College in 1917. Accreditation was received by the California Board of Education in 1927 and administrative control was later transferred to an independent board of trustees in 1933. Following accreditation by the Western College Association in 1955, the school engaged in a vigorous program of innovation during the 1960s with new major programs of study being introduced, such as the introduction of off-campus degree programs in 1969, addition of a law school in 1970, and the American Armenian International College in 1976, plus a name change in 1977 to the University of La Verne. It is a co-educational institution with an enrollment near 1,400.

McPherson College was founded in August of 1887, and opened for classes the following year on September 5, 1888. It was the first of the Brethren affiliated colleges to include a biblical studies program as apart of its origination, and the first to request a direct relationship with the Church of the Brethren. McPherson has a strong agricultural department that was strengthened by the acquisition of a one hundred fifty acre farm in 1909. Accreditation was then received in 1921 from the North Central Association of Colleges. Presently, a board of trustees includes some Brethren from surrounding church districts. Since it is the only Brethren affiliated institution in the mid-west, McPherson serves a wider geographic region than the other five colleges, with a prospective area of coverage from the Pacific coast to the Mississippi River, and from Canada to Mexico. It is a co-educational institution with an enrollment near 500.

Manchester University was incorporated from the former Roanoke Classical Seminary, founded in 1860 by members of the United Brethren Church in Roanoke, Indiana. It was moved to North Manchester, Indiana, in 1889 and acquired by representatives of the Church of the Brethren who incorporated it as the College and Bible School in 1895. Presently it is governed by a board of trustees, some of whose members are elected by various Church of the Brethren districts. Accreditation was received from the State of Indiana in 1932. Manchester was the first Brethren affiliated college to offer a Peace Studies program in 1948. It is a co-educational institution with an enrollment near 1,100.

ultural modifications and innovations of this century had a cumulative effect. As more factors began changing the Brethren subculture, one of three things would usually happen; it would be resisted by those who did not want their heritage altered (the Primitives or Old Orders), it would be celebrated by those who delighted in progress (the Progressives), or it would be grudgingly accepted in silence by the majority (called the Conservatives). Exposure to new ideas and cultural relationships succeeded in making the more primitive Brethren intransigent toward change, whereas the explosion of industrial innovations and variously related opportunities delighted the more liberal Brethren. The neutral high-ground of the vast number of moderates did not provide sufficient calm to inhibit the later secession of both more extreme groups.

ultural modifications and innovations of this century had a cumulative effect. As more factors began changing the Brethren subculture, one of three things would usually happen; it would be resisted by those who did not want their heritage altered (the Primitives or Old Orders), it would be celebrated by those who delighted in progress (the Progressives), or it would be grudgingly accepted in silence by the majority (called the Conservatives). Exposure to new ideas and cultural relationships succeeded in making the more primitive Brethren intransigent toward change, whereas the explosion of industrial innovations and variously related opportunities delighted the more liberal Brethren. The neutral high-ground of the vast number of moderates did not provide sufficient calm to inhibit the later secession of both more extreme groups.

All of the cultural factors enumerated in the preceding sections of this document produced two very separate minority factions during the Nineteenth century. Industrialism, participation in war, and a professional ministry irreversibly changed the inner soul of many Brethren, with the contributing element of Brethren publications quickly transporting these opinions and observations throughout the denomination. Socially forced exposure to new concepts removed the Brethren’s ability to remain sheltered in a protected subculture. Progressives gladly accepted the innovations of this century, and tried to influence their fellow Brethren to do likewise, but the primitives or Old Orders (also called Ancient Brethren) regarded this as a worldly invitation to dismiss proven cherished values, feeling threatened with the loss of control over their heritage. Predictably, each group viewed the other with mild suspicion which only increased the probability of a cultural collision. For many years prior to the schisms, Annual Meeting was the arena of dissidence where Progressives, Primitives, and Conservatives frequently and tearfully collided over parliamentary questions regarding social conventions, methods of worship, and denominational policy.

Something else was gradually changing during this century; a population shift was occurring in which a substantial increase of people resided in more urban areas. In the 1790 U.S. census, only three percent of the population lived in the six largest cities, but in only one-half century, that increased to sixteen percent. More of the Brethren were being urbanized, and agrarianism reflected the life style of fewer people. Gradually a new, more sophisticated face began to appear on the denominational countenance along with a revised system of values. Life in the country, even among non-farming people, is more intricately woven into the process of agriculture, with planting and harvesting accomplished through dependence on favorable weather. Because of this trust on nature, God naturally becomes more central to thought, activities, and planning. Life on the urban scene is an agglomeration of glass, asphalt, steel, brick, stucco, and concrete. Immersed in this ocean of human construction, urbanites naturally depend to a greater extent on ingenuity and social economy than divine providence. Country folk gravitate toward simplicity while city dwekkers run a gauntlet of complexity. If the expanse of open country invites communication and hospitality, the close quarters of town life overwhelms people with fear and distrust. Both natures are subtlety exhibited in beliefs, conduct, dress, expectations, and utilization of materials.

Modernists snicker at the questions of propriety that arose during this century: “Should one permit carpeting?” or “Should one install lightning rods?” or “Should one allow photographs?” But these arguments uniquely reflected the social climate of that day, and the modernist is reminded that similar questions of culture exist today over abortion, civil rights, economic disparity, genetic engineering, and sexuality. Only the labels have changed, for people residing in culturally different localities will predictably disagree over social conventions, ethics, and theology because they perceive their environment and their God much differently.

Culturally different voices gave expression at Annual Meeting representing fundamentally different perceptions of the Brethren experience. The Old Orders or Primitives viewed members, although in separate congregations, as single units of the greater body of the church. Elders supervised individual congregations and stood in harmony with each other at the Annual Meeting; thus, the yearly gathering was esteemed as the ultimate seat of denominational authority. Furthermore, it was held every year on Pentecost, so as to parallel their decision making with the original infilling of the Holy Spirit. This almost mystical association was to hopefully invite the Spirit to, likewise, fill the attendants of Annual Meeting with spiritual wisdom for proper decision making. Additionally, these decisions were arrived through consensus or unanimity of opinion, so as to maintain harmony throughout the body. Conversely, Progressives viewed members as units of autonomous congregations which did not necessarily require a yearly conference; thus, each congregation should be its own seat of authority. Furthermore, the innovation of democratic rule (by majority) at Annual Meeting was heralded as progress, because it hastened parliamentary action, instead of the protracted discussions necessary to arrive at consensus. Unfortunately, this always produces a minority opinion which lacks the unanimity and harmony of consensus enjoyed by the Primitives or Old Orders.

During the 1870’s, a small Progressive group began lobbying the church to implement innovations that were considered by the vast majority of moderates as too worldly. At the same time, a small group of Old Orders desired implementation of measures to preserve historic values that were similarly perceived by the moderates as too restrictive. The insistence of each group to have their own way fractured the German Baptist Brethren. The Old Orders broke away from Annual Meeting in 1881 to form the Old German Baptist Brethren. Minister and publisher Henry R. Holsinger gradually became a firebrand of the Progressives, calling for a series of reforms: salaried ministers, Sunday School, personal choice of dress, unique approaches to missions, greater emphasis on evangelism. He used his various publications to change public opinion. At the 1867 Annual Meeting he erupted over the installation of deacons. The argument became so heated that he was later forced to apologize for many of his statements. This was the first of many incidences that would widened the gap between Holsinger and the Annual Meeting leadership only. Eventually he was disowned by the 1882 Annual Meeting. Progressives supported his causes and seceded to form The Brethren Church at Dayton, Ohio, on June 6, 1883. These divisions actually freed the central group of moderates (then called Conservatives) from the insistence of both parties, to finally regain the momentum of their own denominational vision. But it would take years for that vision to crystallize, because the constant infighting at Annual Meeting had left them without a clear identity.

Although dismayed by the series of events for many years, the moderates gradually devised a course for the future. In the 1904-1906 Annual Meetings they felt the need for a new identity with a new denominational name, for at least three reasons: (1) Brethren had been predominately speaking English since about 1850, (2) the label German gradually seemed less and less descriptive of their evolving culture, and (3) a new label would hopefully disassociate them from the unpleasant divisiveness of the recent past. Originally known as the Schwarzenau Baptists, they assumed the name of German Baptist Brethren in their New World migrations, since few people in America would have any idea where Schwarzenau is located. Much aware that they were no longer strictly German and now also eschewing the title Baptist, the remaining word Brethren was the only thing left that would still retain their heritage. In 1908, Annual Conference (previously called Annual Meeting) would formally adopt the denominational label, Church of the Brethren. They were . . .

Graphic Credits:

- Spring House photo submitted by Richard Judy from The History of the Church of the Brethren: Northeastern Ohio, 1914, and drawn from memory by Irene Kurtz Summers, granddaughter of Elder Henry Kurtz, and retouched by Mrs. F.E. Moherman

- Elder Christian Winey, Bunkertown Church of the Brethren

- Brethren publications images courtsey of Brethren Historical Library & Archives

Bibliography:

- Carl Bowman, Brethren Society, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995

- U.S. Census - Population: Rural-Urban 1790-1990

- Brethren Groups: A Composite View

- The Brethren Church

- Fellowship of Grace Brethren Churches

- Old Order German Baptist Brethren

“This book of the law shall not depart out of thy mouth; but thou shalt meditate therein day and night,

that thou mayest observe to do according to all that is written therein: for then thou shalt make thy

way prosperous, and then thou shalt have good success.”

Joshua 1:8

EARLY BRETHREN PUBLICATIONS

EARLY BRETHREN PUBLICATIONS FRONT

FRONT REAR

REAR

JAMES WATT’S STEAM ENGINE

JAMES WATT’S STEAM ENGINE